Rhetorical Style Analysis of the Statement of Purpose (SP) Genre: A Shared Understanding of Lexis in Successful SPs

by Priyanka Ganguly | Xchanges 16.1, Spring 2021

Contents

Results and Analysis

Results showed that while first-person personal pronouns and simple and loose sentences were used frequently, contractions were used sparingly in my sample of SPs. A combination of long and short sentences and paragraphs was predominant. In the following sections, I provide excerpts from the SPs so that the reader can draw important conclusions from the data. In the excerpts, I did not alter any grammar, punctuation, or capitalization. I chose each example on the basis of its ability to demonstrate the findings accurately and describe the most important phenomena.

Kind of Diction

My diction analysis in the SPs revealed the heavy use of first-person personal pronouns—a finding that I expected at the beginning of my study. In the sample, I found only a few contractions. The implications of the applicants’ rhetorical strategy of using personal pronouns but not using contractions are discussed below.

Use of personal pronouns

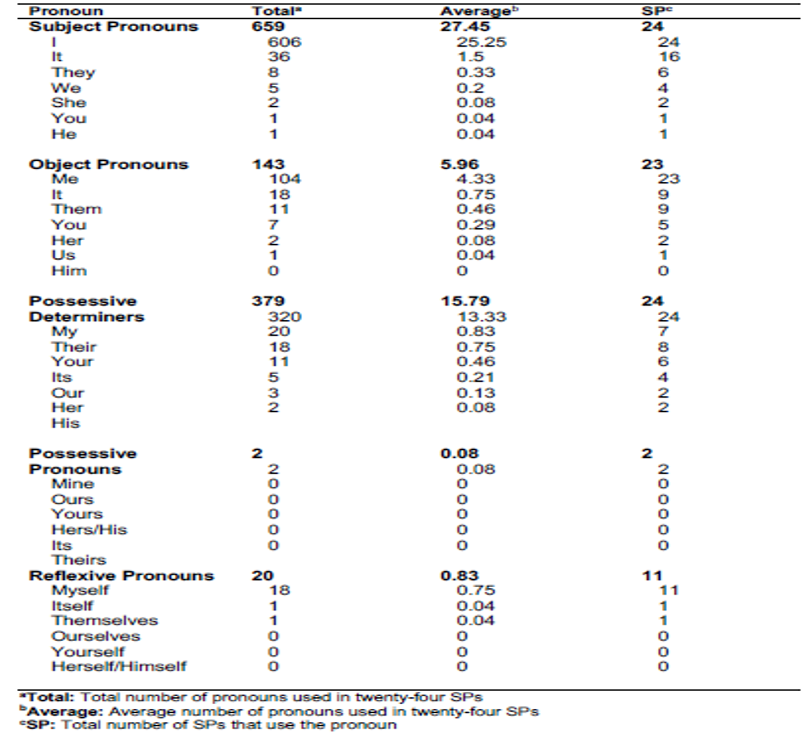

Table 2 summarizes the total number and average number of personal pronouns in my sample and the number of SPs containing a specific personal pronoun. Results showed that first-person pronouns in subjective, objective, and possessive cases and reflexive form were predominant in my sample. In twenty-four SPs, there were 1203 personal pronouns, and 1061 of those personal pronouns were devoted predominantly to first-person singular and plural personal pronouns (I, we, me, us, my, our, mine, and myself).

Among the different forms of personal pronouns, the most prevalent were I as subject pronoun and my as possessive determiner. In their SPs, all participants used first-person pronoun in subjective case (i.e., I), twenty-three in objective case (i.e., me), two in possessive case (i.e., mine), and twenty-four as possessive determiner (i.e., my). Only one participant used second-person pronouns in subjective case (i.e., you), but five used them in objective case (i.e., you) and eight used them as possessive determiners (i.e., your). Second-person personal pronouns in possessive case and reflexive form were entirely absent. The participants in my sample used third-person personal pronouns more than second-person pronouns. Six participants used the third-person plural pronoun in subjective case (i.e., they), nine in objective case (i.e., them), and seven as possessive determiners (i.e., their). One participant used this pronoun in reflexive form (i.e., themselves). No participant used this pronoun in possessive case (i.e., theirs). Sixteen participants used the third-person neutral pronoun in subjective case (i.e., it) and nine in objective case (i.e., it). Six used the neutral pronoun as possessive determiners (i.e., its as in “I wish to develop my career to its fullest potential”) and only one used it in reflexive form (i.e., itself). No subject used this pronoun in possessive case (i.e., its as in “My speed is no match for its”).

My findings suggested that the applicants established ethos (ethical appeal) by using first-person personal pronouns and generally avoiding an impersonal style in their SPs. The applicants used first-person personal pronouns to describe their academic qualifications, skills, professional experiences, and/or other information. I found that some of the applicants used I five or six times in a single sentence. The following excerpts by two participants illustrate this point:

“I understand that the challenges and situations that I will face as a graduate student will be notably different than those that I have faced as an undergraduate, and I look forward to these encounters and to the things that I will be able to learn through them.” “I must admit that this time I do not know exactly what job I will be looking for once I graduate, but I do know that I will have a wider variety of careers to choose from.”

Some of the applicants used my many times in a single sentence in my sample of SPs. For example, one participant wrote,

“I strove to do the best I could in my classes, and my efforts are reflected in my grades and my professors' interest in me as an apt student.”

The pronoun my was used to convey both the applicants’ possessions (for example, grades and classes) and powers (for example, the applicant was able to draw his or her professor’s interest by his or her hard work and expertise) primarily in this sentence.

You as an object pronoun (seven out of 143 object pronouns) was used mostly when the applicants wanted to thank the audience for either reviewing their SPs or for considering their SPs. Through using you as an object pronoun, an applicant was able to show his or her politeness: the applicant showed that he or she really appreciated the audience’s effort in taking the time to review the SP. Additionally, the applicant was able to thank the individual reviewer (i.e., each member of the admission committee individually) as well as the entire committee collectively because both the singular and plural forms of the second person pronoun are you.

The applicants used third-person personal pronouns in greater frequency than they used second-person pronouns. However, the applicants used third-person personal pronouns in much lower frequency than they used first-person pronouns expectedly. Rather than discussing other people or emphasizing others’ influence on their lives by using third-person personal pronouns, the applicants highlighted their own personal accounts by using first-person personal pronouns. My participants used both the third-person personal pronoun they and the third-person neutral pronoun it (i.e., in subjective case) while discussing the organizations, schools, or colleges they worked for and the colleagues and students they worked with in the past; however, the third-person neutral pronoun, i.e., it, was used more often than the third-person personal pronoun, i.e., they.

Use of contractions

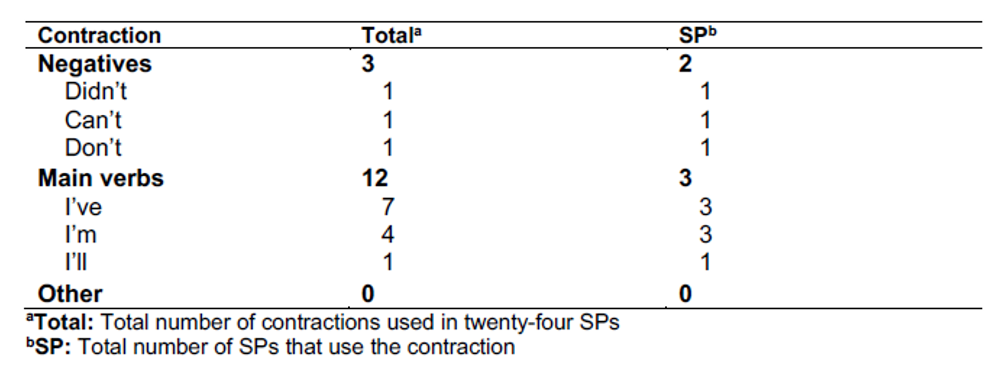

I found that only four out of twenty-four participants (16.67% of all SPs) used contractions. Table 3 summarizes the use of contractions in my sample of SPs. Out of those four participants, three of them used “be” and “have” verbs acting either as main verbs or as helping or auxiliary verbs, for example, “I’m” and I’ve.” Two of those four participants used negative contractions, for example, “didn’t” and “can’t.” However, even these four participants used contractions sparingly, a maximum of five times in an SP. On average, the twenty-four participants used contractions 0.45 times in their SPs.

This absence of contractions from most of the SPs in my sample suggested my participants’ shared understanding of the formality level of the SP genre. Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad, and Finegan (1999) stated that contractions are mostly found in speech and informal and fiction writing, but formal genres like academic texts are not characterized by contractions. Babanoğlu (2017) also stated that contractions result in the “informal tone to writing” (p. 56). Therefore, the absence of contractions from most of the SPs suggested my participants’ tacit assumption about the SP genre: the SP genre is generally perceived as a formal writing genre. However, the SP genre is not a traditional formal writing genre in which contractions, colloquial languages, and first-person personal pronouns are scarcely used (Babanoğlu, 2017; Biber et al., 1999); this genre has its own norms that essentially require first-person writing style.

Sentence Length

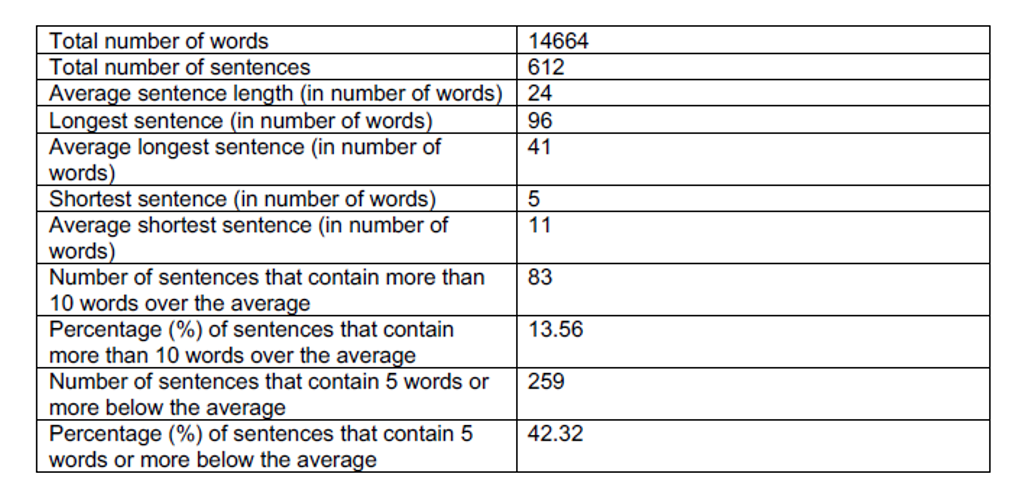

Table 4 summarizes the results regarding the average sentence length and average longest and shortest sentences in twenty-four SPs. I rounded the percentages to the nearest whole number for the sentence length analysis. On average, I found that the applicants used twenty-four words per sentence, which was longer than the average sentence length (eighteen words) in technical prose and technical manuals, as pointed out by Jones (1998, p. 155) and Teklinski (1992). However, the applicants’ average sentence length (twenty-four words) was shorter than sentence lengths common among writers in earlier centuries (Corbett & Connors, 1999). I noticed a significant difference between the longest and shortest sentences in all twenty-four SPs. In my sample, while the longest sentence was ninety-six words, the shortest sentence was just five words. In the sample of twenty-four SPs, the average length of the longest sentence was forty-one words while the average length of the shortest sentence was eleven words. Another notable finding was that the above average sentences were much lower in number than the below average sentences.

Because the MS program in technical communication at this U.S. university does not require any writing sample, the SP plays an important role in understanding the applicant’s writing ability. My participants’ average sentence length (in number of words) suggested that they probably wanted to express their expert level writing skills to the admission committee. Also, clarity—which is inherently associated with style—can be utilized properly by articulating ideas in well-written sentences. Sometimes, complex information cannot be provided in just five words. Therefore, my participants attempted to vary their sentence lengths to showcase their ability to control the long sentences grammatically and use both long and short sentences simultaneously in order to avoid monotony in the writing.

The use of varying sentence length is said to be one indicator of experienced writing. Lu et al. (2018) noticed that native English speakers were more proficient in using varying sentence lengths than non-native speakers. My analysis suggested that, in order to show writing skill in the SPs, the applicants, irrespective of being native or non-native English speakers, attempted to vary their sentence lengths. I noticed two types of strategies of using long and short sentences in my sample of SPs. In the first strategy, an applicant stated a fact by using a short sentence and then supported the fact with evidence in a long sentence. In the second strategy, an applicant took a different approach by placing the supporting arguments in a long sentence and then claiming a fact by using a short sentence.

For example, one participant wrote,

“I would like to apply for teaching assistantship. After graduating with a degree in Chemistry, I taught several courses in Chemistry and Biology at [X] school and [X] academy where I really enjoyed working with students and found out we can only learn more by teaching.”

In this excerpt, the participant first stated that he or she wanted to apply for the teaching assistantship in a short sentence (8 words) and then wrote a supporting statement in a long sentence (38 words) to substantiate his or her teaching experiences and interests.

Another participant wrote,

“Through studying these subjects [communication subjects] I understood how people's needs, aspirations, desires, culture, level of knowledge, socio economic and political background shape the way a person lives and communicates; I believe that communication should be sensitive to all these aspects in order to be successful. And that's what I find highly interesting about it.”1

In this excerpt, the participant first wrote the supporting arguments on why he or she is interested in communication-related subjects in a long sentence (44 words) and then stated the fact about his or her interests in those subjects in a short sentence (9 words).

Only in one participant’s SP did I find that a series of long sentences was used when both stating a fact and supporting it. One exceptional participant continuously used long sentences in his or her SP (an average sentence length of 52 and a longest sentence of ninety-six words). The example of that participant’s longest sentence is as follows:

“Overall, I firmly believe that I would make a strong candidate for the M.S. program for Technical Communication at [redacted]1, especially as a participant in the Graduate Teaching Assistantship, because of the foundational skills I've acquired as an Undergraduate, the distinct opportunity for further academic and professional growth in this particular graduate program, the opportunity to contribute to the department directly through teaching one of the service courses, and the passion that I have for learning the subject matter and applying it in effective ways in the communication contexts in which I find myself.”

In this long sentence, the applicant tried to convince the audience about his or her suitability for a GTA position. In this sentence, the applicant chose three different moves to demonstrate his or her suitability: the applicant’s previous relevant educational background, intention to contribute to the department, and passion for learning from the teaching opportunity. The applicant could have divided this sentence into three separate sentences for the audience, but he or she made the rhetorical decision to use one long sentence (ninety-six words). The applicant’s goal was to obtain a GTA position; therefore, he or she did not want to distract the readers from the single point—that he or she is a suitable candidate for the GTA position—by breaking it into three separate sentences. Interestingly, in my sample, most of the applicants (eighteen out of twenty-four, i.e., 75%) used their longest sentence to prove their suitability for the GTA position. For example, another participant’s longest sentence is as follows:

“I always tried to create an environment for the students to participate in classroom discussion so that they could be eager to learn new things and I could fulfill the goal that I set for every class.”

This sentence indicates the applicant’s previous relevant experience in teaching and eventually demonstrates his or her suitability for the GTA position. This common strategy of presenting information regarding the suitability for a GTA position in one long sentence attempted to achieve one of the following three goals or all the three goals:

- To launch an argument (suitability for a GTA position) and explain that argument thoroughly;

- To create suspense by revealing the main point (suitability for a GTA position) at the end of a sentence; and

- To substantiate an argument (suitability for GTA position) with various and vivid descriptions and proofs, for example, previous relevant experience, passion, or zeal for teaching.

In my sample of SPs, the shortest sentences were used mostly in the introductory and concluding paragraphs. For example, two participants’ shortest sentences are as follows:

“Thank you for reviewing my application.”

“Thank you for your time and consideration.”

In the first and last paragraphs of the SPs, the applicants often used short sentences. More importantly, in those paragraphs, the information was quite simple, not complex. Usually, in the first paragraph, the applicants stated their purpose for writing the SP and discussed their general background, and in the last paragraph, they thanked the audience either for reading their SPs or for reviewing their application materials. These short sentences in the last paragraphs created a polite tone in the SPs either by expressing the desire to apply for the program, by thanking the audience, or by stating their decision for their pursuing graduate study.

In the middle paragraphs, applicants provided more complex information while describing their credentials (academic and professional) and specific reasons for applying to the technical communication program. Therefore, rhetorically it is quite significant that the applicants resorted to long sentences in the middle paragraphs, particularly while walking the audience through narratives of relevant experience and educational background.

Sentence Types

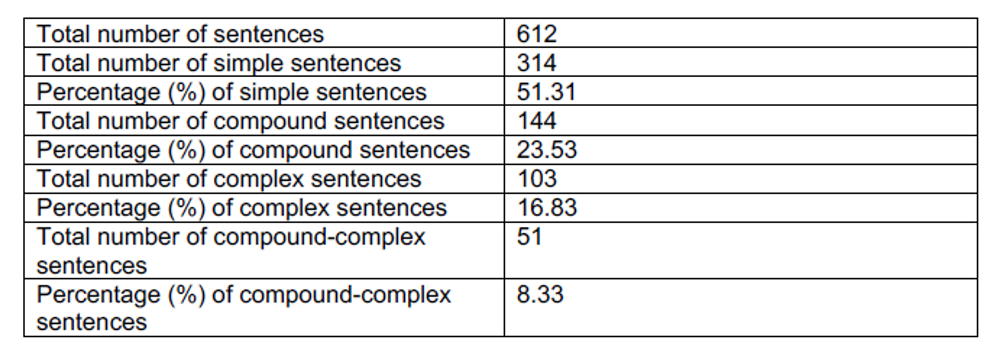

Jones (1998) believed that “sentence variety is essential for achieving an effective style” (p. 155). However, Corbett and Connors (1999) found that modern writers do not always create “a notable variety” in their sentences (p. 363). In my sample, I found that the participants generally varied the grammatical types of sentences in their SPs. Table 5 summarizes my analysis of grammatical types of sentences in twenty-four SPs.

Results showed that simple sentences (51.31%) were more prevalent than the other types of sentences, and compound-complex sentences (8.33%) were less common than the other types. The applicants preferred compound sentences after simple ones in terms of frequency. Complex and compound-complex sentences are considered to be earmarks of an advanced style of writing, and inexperienced writers might make mistakes while creating complex sentences.

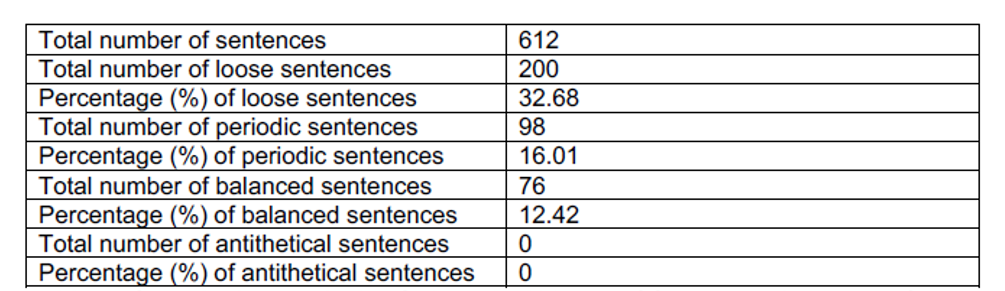

The arrangement of the sentence conveys the rhetorical style taken by the writers (Jones, 1998). Table 6 summarizes the use of rhetorical sentences in twenty-four SPs.

No applicants used antithetical sentences in my sample of SPs. Loose sentences (32.68%) predominated my sample of SPs, and the high frequency of loose sentences indicated the applicants’ choice of maintaining directness, naturalness, and lucidity throughout the SP. Jones (1998) mentioned that loose sentences are “easier for readers to understand because the main clause is at the beginning” (p. 149). Therefore, this high percentage of loose sentences further suggested that the applicants did not want to create any suspense for the readers by making them wait to comprehend the main message until the sentence’s end. Also, since periodic sentences are difficult to comprehend (Jones, 1998), the applicants’ rhetorical strategy of using more loose sentences in their SPs was reasonable.

Paragraphing

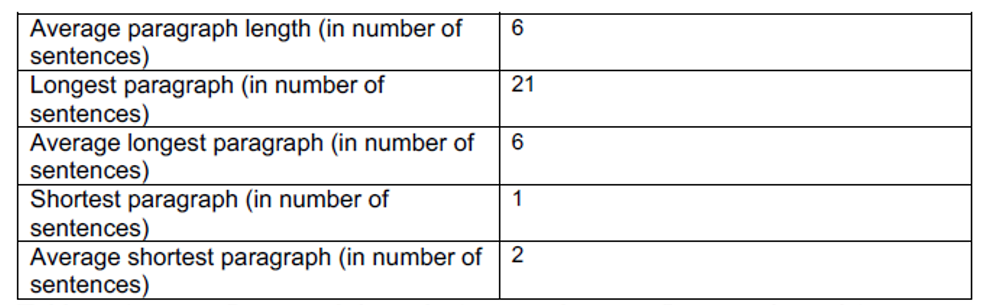

Table 7 summarizes the average paragraph length, average longest paragraph, and average shortest paragraph in number of sentences in my sample (n=24) of SPs. Results showed that my participants averaged six sentences per paragraph, which can be considered as a fairly developed paragraph. Corbett and Connors (1999) found that students in two sections of an Honors Freshman class were generally averaging three to four sentences per paragraph. In my sample, the average paragraph length of almost six sentences suggested that my participants were not unpracticed writers; rather, they already possessed professional writing skills to enter a graduate-level writing program (technical communication).

Similar to the sentence analysis results, I found a significant difference between the longest and shortest paragraphs. My twenty-four participants used six sentences on average for the longest paragraph and two sentences on average for the shortest paragraph (see Table 7). As inexperienced writers are often unable to create substantive paragraphs containing five to six sentences (Jones, 1998), the length of the longest paragraph suggested that the applicants were experienced or proficient writers. The results of my paragraph-level analysis were similar to the results of the sentence-level analysis: the participants varied the lengths of their sentences as well as the lengths of their paragraphs to show writing proficiency.

Interestingly, I also found that most of my participants wrote a single-sentence paragraph in the concluding or last paragraph. For example, one participant wrote,

“To realize my cherished dreams I need a context and association with faculty and people with profound professional skills and that can only happen if my candidature for the Master’s program is considered favorably.”

Another participant wrote,

“I believe I am fully equipped both academically and intellectually to pursue a graduate degree in Technical Communication, and I am very excited to embark upon this journey.”

Another participant wrote,

“Thank you for considering me as an applicant, and I look forward to hearing from you soon.”

According to Corbett and Connors (1999), these sentences do not meet the traditional definition of a paragraph because a single sentence cannot convey a unit of thought large enough to be a paragraph (we should note here that this statement might not be suitable for every genre, for example, the letter genre, where writers often conclude with a single-sentence paragraph). However, these single-sentence paragraphs helped to convey the larger units of thought in other paragraphs in the SP. In the provided examples, the applicants emphasized their enthusiasm for joining the intended program, restated their interest and qualifications in the context of obtaining admission, and politely ended the document by acknowledging or thanking the readers. These single sentences communicated the goal of the applicants’ writing their SPs and brought the readers’ attention back to the main agenda of the SP: gaining admission to the MS program and securing financial support. Additionally, these single-sentence paragraphs acted as attention-getters and transition tools from complicated topics to simple ones (Kolln & Gray, 2019).

[1] The university name is redacted here.

Download PDF

Download PDF