Rhetorical Style Analysis of the Statement of Purpose (SP) Genre: A Shared Understanding of Lexis in Successful SPs

by Priyanka Ganguly | Xchanges 16.1, Spring 2021

Contents

Methods

This article is part of a larger Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved project studying the shared understanding of rhetorical moves, appeals, and style in SPs. Over a period of three months (August 2018–October 2018), I collected a corpus of twenty-seven SPs from both current and former students, including my own SP, submitted to the MS in technical communication program at the same US university. For my stylistic analysis, I examined only twenty-four SPs because the other three SPs (including my SP) were used for the pilot study of the rhetorical-move analysis—one of the parts of my larger study. Also, my sample included only successful SPs submitted to the department from 2005 (the year in which the program began) to 2019 (the year in which I began my research for this study). Because some of the current and former students did not allow me to access their SPs, my sample does not include all the successful SPs submitted to the department since 2005.

The SPs in my sample were written in response to one of two prompts. From 2005 to 2011, applicants were prompted to write a letter of application to the department chair and, in that letter, to state their reasons for applying to the MS program and express their interest in a graduate teaching assistant (GTA) position if they desired funding. From 2012 to 2019, applicants were prompted as follows: “Statement of Purpose: Please type or paste your personal statement of 1,000 words or less here.”

For the stylistic analysis, I followed primarily the subsets of stylistic features proposed by Corbett and Connors (1999), but I did not consider all the features in my study. Corbett and Connors (1999) outlined seven features—kind of diction, length of sentences, kinds of sentences, variety of sentence patterns, means of articulating sentences, uses of figures of speech, and paragraphing—one should look for “when analyzing prose style” (p. 360). In my study, I chose four stylistic markers—kind of diction, length of sentences, kinds of sentences, and paragraphing—to determine the stylistic trends followed by my twenty-four participants in their SPs. For my analysis of diction, I considered each occurrence of a personal pronoun and contraction as the unit of analysis. For the analysis of sentence length and sentence type, I considered each sentence as the unit of analysis. For the analysis of paragraph length, I considered each paragraph as my unit of analysis.

Kind of Diction

Corbett and Connors (1999) suggested looking for the following features of diction:

- Latinate (usually polysyllabic) or Anglo-Saxon (usually monosyllabic);

- Formal or informal; Common words or jargon; Passive or active voice;

- General or specific;

- Abstract or concrete; and

- Referential (denotative) or emotive (connotative). (p. 360)

All these features aid the researcher in analyzing writing style, but, in this article, I focus only on the formal or informal feature for my diction analysis. Regarding formal or informal feature, Corbett and Connors (1999) stated that “Judgments about the formality or informality of a person’s style are made largely on the basis of the level of diction used” (p. 361). The four widely accepted levels of diction are as follows: formal, informal, colloquial, and slang (Jones, 1998, p. 87). However, the identification of accurate levels of diction in a writing might often be subjective; for example, Jones (1998) stated that “colloquial refers to conversation or diction used to achieve conversational prose” (p. 88) and slang is “the most informal” diction and sometimes slang and colloquial dictions overlap. Probably, because of this subjectivity, Markel and Selber (2018) cautioned that there is “no standard definition of levels of formality” (p. 228). Even Jones’ (1998) definitions of formal and informal dictions are subjective: “formal means following an established form, custom, or rule” (p. 87) and “informal refers to ordinary, casual, or familiar use” (p. 88).

Therefore, in order to use the formal-informal distinction in my objective approach to diction analysis, I relied on the definition of formal style in SUNY Geneseo’s Writing Guide (Schacht & Easton, 2008). This guide gives us the quantifiable markers for analyzing the formality of writing style. The guide suggested that formal prose has the following features:

- Conservative (adherence to professional writers’ and editors’ stamp approval);

- Contraction-free (absence of contractions);

- Restrained (absence of coarse language and slang);

- Impersonal (absence of personal pronouns); and

- Properly documented (adherence to standard forms of documentation)

Among these features, I focused on contractions and personal pronouns for my diction analysis. Because in academic writing genres (for example, research papers) contractions are scarcely used (Babanoğlu, 2017), I assumed that it would be worth studying whether the SP writers used them frequently or infrequently. Additionally, contractions are easily quantifiable, and the previous scholars hardly studied them “as a linguistic item” in academic writing genres (Babanoğlu, 2017, pp. 56–57). Although SUNY Geneseo’s Writing Guide (Schacht & Easton, 2008) claims that formal writing follows an impersonal style by avoiding “I,” “me,” and “my,” I was confident that the SP writers used personal pronouns heavily because it is hard to state an applicant’s purpose for graduate school in the third person. Therefore, I intended to understand the quantity and types of personal pronouns used by the applicants to establish a personal style and the frequency of contractions used to establish either a formal or informal writing style in their SPs.

Use of Personal Pronouns

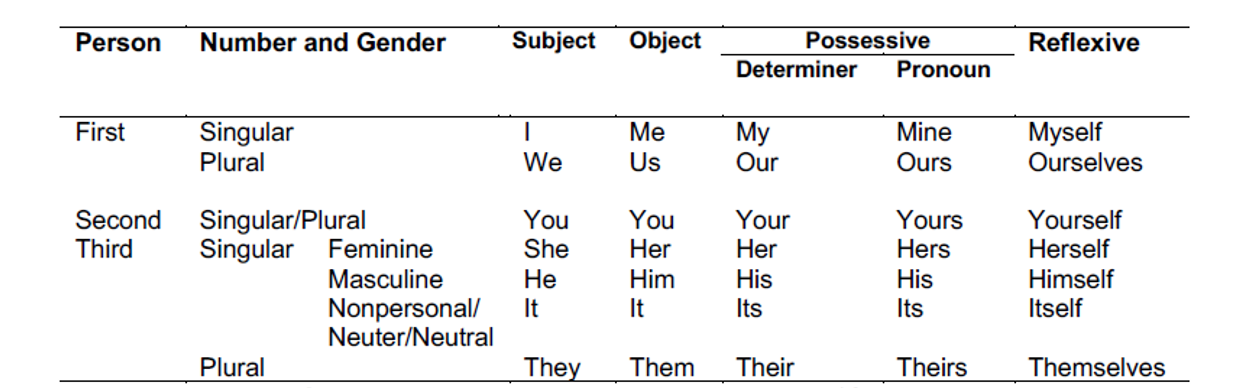

Pronoun usage indicates the way audiences are perceived and conceptualized by speakers and writers in academic discourse (Fortanet-Gomez, 2004)—or, as in my study, how my participants conceptualized the audience (admission committee) of their SPs. More specifically, considering Casañ-Pitarch’s (2016) framework, I intended to analyze how personal pronouns were used in a rhetorically persuasive style. In my analysis of personal pronouns (taking the place of specific persons, groups, or things in terms of person, i.e., first, second, and third, number, gender, and case), I followed the classification systems of Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech, and Svartvik (1972, 1985) and Casañ-Pitarch (2016) (see Table 1). I treat possessive pronouns and reflexive pronouns as types of personal pronouns. Moreover, I separate the possessive pronouns into possessive determiners (my, her, their, etc.) and possessive pronouns (mine, hers, theirs, etc., sometimes called nominal pronouns or absolute possessive pronouns).

First- and second-person pronouns are directly related to the author and the audience, so I focused on these two types of pronouns in this study along with third-person personal pronouns. Also, first-person pronouns help in understanding the “specific attitude” of a writer’s involvement or responsibility (Casañ-Pitarch, 2016), and second-person pronouns involve directness (Williamson, 2006). Third-person pronouns, though not directly related to the reader and the writer, still play a major role in understanding the style of a person’s writing by showing whether the writer uses “indirectness” (Cornish, 2005). Similarly, the study of neutral pronouns (i.e., it, its, and itself, which refer to things, animals, or ideas) gives us an idea how many times a writer uses neutral pronoun forms to refer to “direct and indirect ideas or things within the text without revealing the identity of these” (Casañ-Pitarch, 2016, p. 41). These pronouns are traditionally classified as neuter or nonpersonal in grammatical gender, and I included them, along with other third-person personal pronouns, in my study. Although Klammer and Schulz (1992, p. 88) stated that only pronoun person, gender, and number are relevant when studying diction, I also considered case: “case is determined by the pronoun’s function in the sentence—subjective, objective, or possessive” (Kolln & Gray, 2019, p. 208).

For both quantitative and qualitative analysis of pronouns, I followed Casañ-Pitarch’s (2016) four-step protocol:

- In the first step, I counted the personal pronouns in each SP; results were presented as frequencies (average);

- In the second stage, I classified those pronouns into categories according to case and/or some other property: subject pronoun, object pronoun, possessive pronoun, possessive determiner, and reflexive pronoun;

- In the third stage, I determined each pronoun’s person, number, and gender; and

- Finally, I compiled the results in a tabulated form and qualitatively analyzed the main uses of pronouns in the SP genre and the reason behind emphasizing certain types of pronouns.

Use of Contractions

I chose to analyze the use of contractions along with personal pronouns to find out if the applicants attempted to create a formal or informal style in their SPs. Although the definition of a contraction is widely accepted, I use Jones’s (1998) definition in this study: “A contraction is a shortening of a word, syllable, or word group by omission of a sound or letter. An apostrophe is used to substitute for the missing letter or letters: can’t for cannot; shouldn’t for should not” (p. 99).

Not only does SUNY Geneseo’s Writing Guide (Schacht & Easton, 2008) confirm that contraction-free writing belongs to the formal style, but also other scholars, such as Jones (1998) and Kolln and Gray (2019), argue that contraction-free writing creates a formal writing style. Jones (1998) stated that, if a writer wants to “achieve an informal style” (p. 99), then he or she should use contractions. Kolln and Gray (2019) also stated that contractions aid in a “more conversational, less formal” writing style (p. 182).

In this study, I modified and used the categories suggested by Kolln and Gray (2019) when I was identifying contractions in my sample:

- Negatives, for example, don’t (do not), can’t (cannot), isn’t (is not), hasn’t (has not), shouldn’t (should not), and won’t (will not);

- Main verbs (usually be or have) or helping verbs (i.e., either primary auxiliaries, be, have, and do, or modal auxiliaries), for example, you’re (you are), I’ve (I have), he’s (either he is or he has), she’d (she had or she would), it’s (it is or it has), and I’m (I am); and

- Other, for example, ma’am (contraction of a noun), o’clock (contraction of a preposition and omission of an article), and ’tis (contraction of a pronoun).

I did not expect to find any contractions in the “Other” category in my sample of SPs because these contractions are fairly uncommon in most writing situations.

Length of Sentences

I used MS Word to determine the length of each sentence in each participant’s SP by counting the words in a given text by using spaces between words as separators, when I highlighted each sentence separately. The length of each sentence was measured in number of words. At first, I calculated the average length of sentence (total number of words/total number of sentences). Then, I identified the longest and shortest sentence (in number of words) in each SP. Lastly, I calculated above- and below-average sentence lengths following Corbett and Connors (1999). They define an above-average sentence as more than ten words over the average sentence and a below-average sentence as five words or more below the average sentence (p. 370). The goal of this quantitative-sentence-length analysis was to make a “tenable generalization” (Corbett & Connors, 1999, p. 361) about my participants’ use of sentence length in their SPs and to understand the relationship between sentence length and rhetorical situation. Also, my goal was to understand if applicants used varying sentence lengths in their SPs because variations in sentence length play an important role in establishing an effective style (Jones, 1998). Jones (1998) believed that, particularly in technical writing, “too many short sentences” create a “choppy style” and “too many long sentences” create a “wordy style” (p. 155).

Sentence Type

To understand the syntactical style of the SPs in my sample, I focused on the grammatical and rhetorical types of sentences. The grammatical types of sentences are simple (one independent clause), complex (one independent clause and one or more dependent clauses), compound (two or more independent clauses), or compound-complex (two or more independent clauses and one or more dependent clauses). The rhetorical types of sentences are loose (main idea or clause placed first and one or more subordinate clauses at the end), periodic (main idea or clause placed later in the sentence), balanced (a pattern is repeated at the beginning and in another place in the same sentence), and antithetical (a balanced sentence making a contrast), based on the arrangement of the material.

For my analysis of sentence types, I primarily coded each type of sentence as either one of the grammatical types or one of the rhetorical types, for example, “simple” or “loose,” with a few exceptions. Because a sentence can be more than one type, I coded some of the sentences as both periodic and balanced (Jones, 1998). For example, one applicant wrote,

“Because l can see that good communication can significantly benefit these environments whether through documentation, presentations, or informal discussions and because I know that I have many key skills and experiences that enable me to communicate in a particularly effective fashion in each of these cases, I have developed an intense desire to seek out methods through which I may contribute to the improvement of communication practices in as many sectors of industry as possible.”

After coding, I counted the total number of occurrences of each sentence type and then calculated the percentage by using the following formula:

(Total Number of Occurrences of a Sentence Type/Total Number of Sentences) X 100

In the case of those sentences containing both periodic and balanced types, I counted the sentence once as periodic and once as balanced. For the grammatical sentence analysis, I did not need to consider occurrences within each sentence because each sentence was only one of the following: simple, compound, complex, or compound-complex.

Paragraphing

I identified paragraphs in one of three ways: either by indentation of the first line of a block of text, extra line spacing between blocks of text, or a substantial gap between the end of a sentence and the right margin. In my sample of SPs, my participants used extra line spacing between paragraphs far more often than first-line indentation to demarcate paragraphs. Thus, when the first line of a paragraph was not indented but there was extra line spacing between paragraphs, I assumed that the extra line spacing was for paragraphing. In an SP with no first-line indentation or extra spacing between paragraphs, I looked for a larger-than-normal gap between the end of a sentence and the right-hand margin. In those cases, I considered the next sentence as the beginning of a new paragraph. When an SP consisted of a single block of text, I considered that block of text to be a standalone paragraph. After identifying paragraphs, I calculated the average paragraph length (total number of sentences/total number of paragraphs), average longest paragraph, and average shortest paragraph in twenty-four SPs.

Download PDF

Download PDF