Reimagining Activist Data: A Critique of the STOP AAPI HATE Reports through a Cultural Rhetorics Lens

by Dan Harrigan | Xchanges 16.1, Spring 2021

Contents

Outlining the STOP AAPI HATE Initiative

Linking the STOP AAPI HATE Reports and Cultural Rhetorics

Assembling a Cultural Rhetorics Methodology: Decolonial, Indigenous, and Feminist Theory

Critiquing the STOP AAPI HATE Reports

Reimagining Future Options for STOP AAPI HATE Data

Imagining a Cultural Rhetorics-Informed Future for Technical Communication

Critiquing the STOP AAPI HATE Reports

With explanations for this project’s context, cultural rhetorics connections, and corresponding methodology, I am now prepared to offer informed critiques of the STOP AAPI HATE initiative’s data collection and presentation methods. The following critiques, drawn from my cultural rhetorics methodology, focus on how the STOP AAPI HATE initiative uses the sensitive stories of AAPI victims during the COVID-19 pandemic. More specifically, I would like to turn a critical cultural rhetorics-informed lens towards the initiative's data/story gathering process (the incident reporting form) and the presentation of such data/stories (in the summative report, a technical document). While all three summative reports are markedly similar in terms of format and presentation, for clarity’s sake I will be focusing my critiques on the incident reporting form as it appeared on May 1st, 2020.

Data Gathering Critiques

With its incident report form, the STOP AAPI HATE initiative generalizes and erases nuance from AAPI stories by presenting the user with an abundance of “checkbox questions” and by offering limited space for free writing. “Checkbox questions” require the user to select their answers from a provided list of one or more prewritten choices. For example, the incident reporting form requires the user to answer “checkbox questions” regarding the site of discrimination, type of discrimination, and suspected reason for discrimination, even though all three questions could yield unique, layered answers (see Figure 2).

In technical communication, the checkbox-question tactic generally makes data interpretation easier by readily sorting user submissions into easily discernible categories. However, in this context, where the central content of the gathered data consists of stories told by a vulnerable population, the use of checkbox questions does not allow that population to tell their own unique, silenced stories. Innis (2002) claims that “Colonial projects ... move forward by devising and reinforcing categories...routinely silencing local traditions that do not fit [in]” (Cruikshank, pp. 6-7). I am by no means labeling the STOP AAPI HATE initiative a “colonial project”; however, it is clear that checkbox categorization does effectively generalize stories that don’t fit cleanly into said categories. It should be noted that the incident report form does encourage the user to check more than one box if their experiences apply to multiple categories, and the “Type of Discrimination” field contains an “other” option where the user can freely write out their own discrimination experience. However, the presence of suggested checkbox options indirectly implies that there are preferred, dominant answers to these questions.

Additionally, near the bottom of the incident reporting form, there is space for a user to freely write out their own “Description of Incident” (as shown in Figure 2). While this prompt does allow for direct storytelling, it also imposes digital limitations on the storyteller. For example, the prompt instructs the user to keep their responses to “2-3 sentences,” effectively restricting their storytelling space. Moreover, the prompt only provides a single “fill-in-the blank” line for responses, indirectly curtailing the length of typed responses. Upon looking critically at the incident report form’s reliance on checkbox questions and limited free-writing space through a cultural rhetorics lens that prizes the inclusivity of all perspectives, I assert that the form’s current structure discourages the user from telling their own unique stories.

By using primarily the English language on the STOP AAPI HATE website, incident reports, and summative reports, the initiative risks silencing the stories and experiences of non-English speakers. Despite offering access to its incident reports in 12 different languages as of May 2020, it is clear that the STOP AAPI HATE initiative consistently uses the English language to convey their activist messages in other areas of the site. For example, the AP3CON website, which contains the main link to the incident report forms, is primarily available to the public in English. Although many current web browsers (such as Chrome, Firefox, and Microsoft Edge) offer the option to translate web text to other languages, some important elements of the AP3CON website, such as the “COVID-19 Resources” tab, cannot utilize these translation options due to their HTML formatting.

This translation issue also extends to the STOP AAPI HATE technical documents, as both the summative reports and press releases are written in English and disseminated as PDF files, which cannot be freely translated into other languages. The limited availability of non-English documents means that both summative report data and general news of this initiative often fails to reach non-English speaking AAPI communities, thus limiting their access to STOP AAPI HATE’s valuable movement. In the initiative’s first summative report, published on March 25th, 2020, only 5.5% of incident reporters classified themselves as limited English speakers (Jeung, p. 1). This English-speaking statistic, which interestingly isn’t brought up in future summative reports, demonstrates how this initiative’s reliance on the English language has hampered its positive influence and reach towards silenced, non-English speaking AAPIs.

By only offering the reports and press releases in English, the initiative is effectively restricting non-English speaking access to their movement, silencing potential stories that could be told from those populations. Additionally, it should be noted that each non-English incident report form actually still uses English for the prompt labels, noting the appropriate translations in brackets (see Figure 2). This design choice to list the English translation first, before the native language, seemingly implies that English is the dominant language of the forms, with other languages viewed as secondary additions. Again, this choice indirectly discourages non-English speakers from submitting responses in their native languages, reinforcing a dichotomy where English is the dominant, preferred language choice over its non-English counterparts.

Even though the STOP AAPI HATE initiative provides a disclaimer regarding the confidentiality of user information on its incident report form, the movement showcases a lack of reciprocity by being unclear about how it will utilize that information. As Johnson (2016) states, “User advocacy is not fully enacted by merely making objects easy to use but also includes respecting users enough to convey effects of use so they can make informed decisions” (Jones et al., p. 218). While incident report forms are readily available to much of the AAPI population, the initiative remains somewhat vague on how these AAPI stories (and other required user information) will be utilized beyond the summative reports, stating that its main mission is “... to provide resources for impacted individuals and to advocate for policies and programs dedicated to curtailing racial profiling” (Choi and Kulkarni, 2020, para. 4). However, to my knowledge, as of May 2020, the initiative has not yet released specifics of these resources, policies, and programs to the public.

From the cultural rhetorics perspective of reciprocity, the STOP AAPI HATE is not, according to Smith (1999), “reporting back” to its users regarding progress towards its goals--users submit vulnerable stories and hear silence on the other end (p. 15). As a personal example, when I submitted my own incident report form to the initiative, I received nothing in return, not even a simple email acknowledgement (which, to my knowledge, can even be automated) of my submission. This current unequal transaction model, in which an AAPI user submits a valuable story only to hear silence on the other end, further clashes with Wilson's aforementioned Indigenous research tenets of respect, reciprocity, and responsibility (2008, p. 77).

The need for transparency is made more urgent by the initiative’s intrusive incident reporting requirements. For instance, to successfully submit a report, the user must first provide their first name, last name, age, email address, ethnicity, state, and zip code within the form. And while the initiative does state that this information will be kept confidential, with this information used for “data purposes,” they remain vague regarding their use and storage of such sensitive digital information. In return for offering their sensitive information and stories, users should at least be able to expect a heightened degree of transparency from the STOP AAPI HATE initiative regarding data usage, storage, and broader organizational progress in these uncertain times.

Data Presentation Critiques

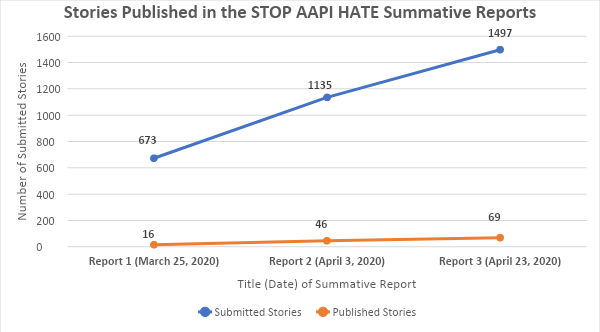

My primary critique in this section centers around the STOP AAPI HATE initiative’s practice of selectively publishing stories within each of their summative reports, effectively silencing many AAPI voices and perspectives in the process. As seen in Figure 7, an alarmingly limited number of AAPI stories (approximately 4% of all submitted stories) get published within the summative reports.

According to Banks et al. (2019), this filtration of stories demonstrates how the initiative “... [orients] toward the objects, participants, or contexts of study. These orientations speak ... about who is in charge of collecting data, what counts as data, and which objects ... have value” (p. 3). By engaging with this selective publishing system, the STOP AAPI HATE initiative indirectly implies that they value certain AAPI stories over others, their exact measurements for story publication remaining unclear.

By taking up this selective role, the initiative occupies a position of power over the user, as it ultimately decides which voices get to be heard by the broader AAPI community. This unequal arrangement not only clashes with the main objective of cultural rhetorics, which again recognizes the equal value of all cultures and their stories, it also showcases how seemingly “neutral” data, presented as factual, can be influenced by decisions from those in power. As Haas (2012) states, “Technologies are not neutral or objective—nor are the ways that we use them” (p. 288). By encouraging user responses with their incident reporting forms and then choosing which of those submitted stories get published, the STOP AAPI HATE initiative silences a majority of submitted AAPI accounts. Additionally, I should note that it is unclear what happens to the stories that do go unpublished -- perhaps they are stored for future usage or discarded, for example. While the current reporting format understandably restricts how many stories can be published in each summative report, the initiative could be more transparent with their decision-making process and storage policies when it comes to publishing (or not publishing) AAPI experiences.

By publishing AAPI stories exclusively in English and by sorting them into preset categories, the STOP AAPI HATE summative reports seemingly translate AAPI perspectives to fit categorical needs, stripping storytellers of their unique voices. While the potential exclusion of non-English stories is definitely a discouraged move within the field of cultural rhetorics, translating those stories to English from their home languages is almost equally as problematic. Maracle (1990) explains this problem through the Indigenous lens of story, stating that, by preferring the English language to convey stories, “... the speaker (or writer) retains authority over thought. By demanding that all thoughts ... be presented in this manner ... the presenter retains the power to make decisions on behalf of others” (p. 11). By not being transparent in regard to whether the published stories are altered or translated, the STOP AAPI HATE initiative retains interpretive power over the types of messages being conveyed in the summative reports. This issue extends to the initiative’s practice of sorting stories by different types of discrimination within the report (reference Figure 6). As Cruikshank (2002) asserts, excessive categorization of archival data can “... reduce complex stories to simple messages” (p. 22). Applying this knowledge to the summative reports, this practice of categorization means that the initiative must always select a single category for a published story, regardless of whether the AAPI user clicked multiple checkboxes under the “type of discrimination” option. Again, I am not claiming that this activist initiative has any ill intentions with their current treatment of AAPI stories. However, I do believe that STOP AAPI HATE could be more transparent regarding if (and if so, how) they edit non-English stories before sorting them into designated categories, which is another potentially problematic practice.

Further extending my critique of the STOP AAPI HATE initiative’s overall transparency, I personally find it troublesome that much of the user data submitted to the initiative is not made consistently visible in the final summative report. To reiterate one of my previous points, the vulnerable AAPI storytellers who participate in this movement deserve to know how their data is being utilized by the initiative, especially after viewing the elements presented in the final summative report. For instance, the incident reporting form requires the user to submit their full name, zip code, and email address before submission. However, none of these elements (understandably) are present in the final summative reports, so one is left wondering why the initiative would ask for this confidential information in the first place.

Approaching this issue from another angle, each summative report begins with a press release that highlights specific data trends from week to week among the submissions. However, the initiative seems to pick and choose which trends to highlight in each report, with some trends (such as the percentage of limited-English submitters referenced in Figure 3) disappearing from the following reports. Additionally, while much of these trends can be interpreted with the reports’ included and available data, the initiative occasionally pulls these trends from data, which is not accessible to the public, such as the “language chosen” in each report and the “daily number of reports.” By drawing from data that is inaccessible to its users while also only publishing certain trends from week to week, the STOP AAPI HATE initiative retains control over the broader narratives that are derived from their data.

Additionally, when looking at the visual design of these reports, the initiative still relies too heavily on alphabetic and numeric text to convey data reinforced with its use of text-filled tables and typed-out trends. As Powell et al. (2014) state, “... human practices and makings are often reduced to texts, or to textual objects, in a way that elides both their makers and the systems of power in which they were produced” (p. 6). Thankfully, the reports have started to include graphed visuals as a data interpretation alternative to the English text (reference Figures 4 and 5). However, by not maintaining consistency with their data presentation and availability, the initiative ultimately retains control over the narratives told within its summative reports. While the STOP AAPI HATE reports reflect many aspects of cultural rhetorics, viewing the data collection and presentation practices that make up the reports through the same decolonial lens exposes certain information gathering and design practices for both critique and suggestions for improvement.

Download PDF

Download PDF