"Where Is He?!: Asian/American Representation in Netflix Original Programming"

by Anthony Lerner | Xchanges 15.2, Fall 2020

Contents

Results

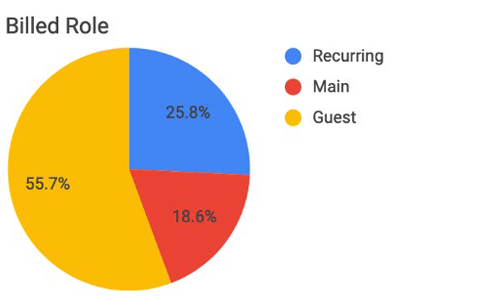

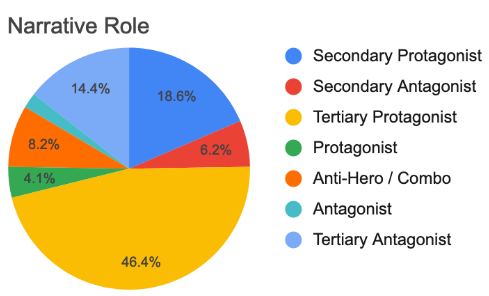

To get a sample of 30 programs, I used the random number generating site several times. Ultimately, I had to draw 53 programs total because 23 of these programs (43.3%) did not have a single Asian/American character. Out of the 30 that did, 29.3% were comedies, 29.3% were dramas, and 41.5% were of indeterminable program genres. Fourteen of the programs were films, and 16 were television shows. Within the 30 programs, a total of 97 characters were coded. Sixty-nine of these characters had names they were addressed by (71%). For a visual breakdown of Asian/American character roles, see Figures 1 and 2.

Note. Characters based on IMDb billing. N = 97; Main = 18 (18.6%), Recurring = 25 (25.8%), Guest = 54 (55.7%). The most common ethnicities of the characters were Unspecified East Asian (40.2%), Unspecified South Asian (21.6%), and Korean (12.6%). Gender was almost evenly split between cisgender women (50.5%) and cisgender men (49.5%). While immigrant status of most characters were unspecified (77.3%), if it was specified, it was an immigrant (7.2%), rather than someone who was second/third generation (0%).

Note. Characters based on their role in the program. N = 97; Protagonist = 4 (4.1%), Antagonist = 2 (2.1%), Secondary Protagonist = 18 (18.6%), Secondary Antagonist = 6 (6.2%), Tertiary Protagonist = 45 (46.4%), Tertiary Antagonist = 14 (14.6%), Anti-Hero / Combo = 8 (8.2%).

If jobs were specified (37 out of 97 were not), the most common were doctor and nurse. The next most common were spa workers. Following this, a majority of positions were under the pink collar/reproductive labor category. See Table 1.

|

# of Characters |

Occupation |

|

37 |

N/A |

|

5 |

Doctor, Nurse |

|

4 |

Spa Technicians |

|

3 |

Cashier, Royalty, Unspecified Office Jobs |

|

2 |

Businessmen, Celebrity Chef, Criminal, Farmer, Heating/Technician, News Host, Police Officer, Restaurant Owner, Teacher, Wrestler |

|

1 |

Activist, Canoe Instructor, College Admissions Officer, Customs Officer, Director, Director’s Assistant, Engineer, FBI Agent, Laundromat Owner, Rabbi, Screenwriter, Socialite, Stripper, Therapist, Valet, Web Designer |

Table 1: Occupations of Asian/American Characters Coded

With personality variables, the most commonly coded answer was “Unknown,” meaning that the character was not on screen long enough for anything about the proposed personality variables to be discerned. Consequently, we see a range from 17.5% (Extroverted) to 75.3% (Formal Religion) and 83.5% (Humanities Prowess) of characters coded as “Unknown,” meaning they were not fleshed out enough to determine whether they held that personality trait or not. The largest number of definitive codes for personality variables was 61.9% (Extroverted, Y). See Table 2.

|

Personality Traits |

Were Characters Depicted as Such? |

||

|

Y |

N |

Unknown |

|

|

Duplicity |

23 (23.7%) |

37 (38.1%) |

37 (38.1%) |

|

Ambition |

17 (17.5%) |

17 (17.5%) |

63 (64.9%) |

|

Selfishness |

28 (28.9%) |

23 (23.7%) |

46 (47.4) |

|

Extroverted |

60 (61.9%) |

20 (20.6%) |

17 (17.5%) |

|

Spirituality |

4 (4.1%) |

22 (22.7%) |

71 (73.2%) |

|

Formal Religion |

2 (2.1%) |

22 (22.7%) |

73 (75.3%) |

|

Prowess – Education |

8 (8.2%) |

12 (12.4%) |

77 (79.4%) |

|

Prowess – Business |

18 (18.8%) |

8 (8.3%) |

70 (72.9%) |

|

Prowess – STEM |

15 (15.5%) |

10 (10.3%) |

72 (74.2%) |

|

Prowess – Humanities |

13 (13.4%) |

3 (3.1%) |

81 (83.5%) |

|

Prowess – Social Skills |

60 (61.9%) |

24 (24.7%) |

13 (13.4%) |

|

Displays Emotions – Happiness |

57 (58.8%) |

36 (37.1%) |

4 (4.1%) |

|

Displays Emotions – Sadness/Grief |

30 (30.9%) |

62 (63.9%) |

5 (5.2%) |

|

Displays Emotions – Anger |

28 (28.9%) |

65 (67.0%) |

4 (4.1%) |

|

Displays Emotions – Fear |

24 (24.7%) |

69 (71.1%) |

4 (4.1%) |

|

Displays Emotions – Empathy/Sympathy |

42 (43.8%) |

51 (53.1%) |

3 (3.1%) |

|

Displays Emotions – Guilt/Remorse |

14 (14.4%) |

77 (79.4%) |

6 (6.2%) |

Table 2: Personality Variables of Asian/American Characters Coded

Within the Duplicitous personality variable, characters were coded as Unknown (38.1%), N (38.1%), Y (23.7%). While cisgender men and women were nearly equally likely to be not-duplicitous (17 men, 20 women), cisgender women were more likely to be duplicitous (15 women to 9 men). It did not matter what billed or narrative role a character had in determining their duplicity, but characters who were specified as immigrants were shown to be more duplicitous than not-duplicitous (5 out of 7 characters versus 2 out of 7).

In regards to level 5 (relationship) variables, a majority of characters were coded as “N” for a lack of any sexual or romantic behaviors or conversations. Out of the behaviors, Light Kissing/Touching was most commonly coded as “Y” (16.5%); out of conversations, Building/Maintaining a Relationship was most commonly coded as “Y” (21.6%). If we break these variables by gender, cisgender men are more commonly coded as “Y” than women in talk regarding Building/Maintaining a Relationship (13 versus 8), but cisgender women slightly more frequently than men mention Liking/Loving Someone (9 versus 7) and Words Insinuating Sex (9 versus 3). Within the behaviors category, cisgender women slightly more frequently than men exhibited traits coded in the following categories: Dating/Courting (5 versus 4), Light Kissing/Touching (9 versus 7), Physical Flirting (8 versus 5), Passionate Kissing (2 each), Intimate Touching (3 each), Implied Intercourse (2 versus 1). Cisgender women were coded as the initiator 8 times versus men’s 4, and cisgender men were coded as the ones whose partners were the initiator for 6 times versus cisgender women’s 5.

Autoethnography

As I watched each film, I remained cognizant of my own reactions. While the story in the introduction is the most extreme of my experiences coding for this study, it is by no means an outlier. A majority of the programs I watched (25 out of 30) only had a couple of scenes with an Asian/American character in them at all. For these programs, I could easily fast-forward through a majority of the program without needing to pause and code too often; showing that even if Asian/Americans are present, the characters do not have much of a presence. If they did, it felt very subservient towards the growth of the main (white) character. In one of the episodes of Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt (2019), for example, the Korean nail techs introduce Kimmy to white privilege. In Love (2016), the Asian/American characters serve as nuisances or downright adversarial coworkers to the protagonists. If the Asian/American characters are not subservient to the growth of the main character, they served as comedic gags. In Girlboss (2017) this was especially the case—all four Asian/American characters were written in this way. The nurse who greets Sophia when she arrives in the hospital for a medical emergency grins foolishly and proclaims, “Okay, I need to shave down there!” It is supposed to be absurd to the audience that this nurse knows about what lies down there, or that she is allowed to be near that area. One of the doctors who treat Sophia is made fun of for his eyebrows and is considered ugly compared to his white counterpart. Kaavi the web designer and Edwin the laundryman are emotionless robots who serve to propel Sophia to be the great online fashion mogul she is surely destined to become, reiterating scholarship that articulates how Asian/Americans can only tend the terrain of American society and bolster its (white) inhabitants, but never partake themselves (Yoon, 2008).

The Asian/American characters that did not fall under either of the previous two categories were infused with stereotypes. While Sense8 (2015) is filled with domineering albeit still emasculated husbands for their token Indian characters, and an oppressed daughter to serve as their token Korean character, Daredevil (2016) has a living, breathing dragon lady in Elektra Natchios . One of two love interests for lead Matt Murdock, Elektra is a sharp contrast to blonde, demure Karen Page. While Karen and Matt only kiss at the end of their first date, Electra is a thrill seeker who is also extremely sexual. In the climax of their relationship, Electra tricks Matthew into breaking into the house of his father’s killer, before encouraging Matthew to murder the man in question. “There was always this glorious darkness inside of you,” Elektra tells Matthew with the guiltless smile of a sociopath. “That’s why I loved you. That’s why you loved me too. Don’t deny what we have.” She is the exotic East in one character, blowing off money without care and cajoling out a dark side to Matthew that would not have, apparently, come to light without her influence, reaffirming notions of Asian/American women throughout American history and culture (Shimizu, 2007; Marchetti, 1993). There is no mention of her past, her hopes, her dreams. I swore that I could feel my blood boil in my veins the more I watched.

The stereotypes woven into the character of Tam in The Cloverfield Paradox (2018) are not as obvious, but still just as jarring to witness. An engineer from China, Tam is the only character to speak solely in her native language of Mandarin. While there are German and Brazilian crew members on the space shuttle, neither of them speaks solely in German or Portuguese. The entire time she is on screen, she seems subservient to the needs of her German partner, Kiel, and doesn’t seem to have many needs of her own. Despite an emergency of horrific proportions on the space shuttle, not much care is given towards how Tam is feeling about her circumstances. She is tasked with both fixing the problem and, somehow, despite being an engineer and not a doctor or a mortician, cutting open the body of a dead crew mate for horror film shenanigans. She is not even allowed to blink at the terrors she is put through, even when she is murdered: her last act is to tragically put her hand against the glass that separates her from the others to meet Kiel’s. Tam is treated as an alien the most, though, when a white, blonde woman, Mina, from a parallel universe is dragged into the universe of the main cast. When she sees Tam, a truly disturbed and fearful look crosses her face. “I know everyone,” Mina says, “everyone except her.” In my seat, I felt slightly nauseous at the way the syllables of her words twist into disgust (Chu, 2015). “Who is that woman?” It turns out, in Mina’s original universe, she has Tam’s job. After Tam drowns, Mina takes her place, implying that Tam is secondary to Mina, tending to her position at the expense of herself (Yoon, 2008).

Even in nearly all of the five programs that I did not have to fast-forward through, there seemed to be a catch with each of their representations. In Dude (2018), the character of Rebecca is given a white best friend to heavily support and a likely illegal relationship with her teacher. Her mother and father appear so briefly at the end of the film that they are not even credited in IMDb. Within the film Rim of the World (2019), the main female lead, Zhenzhen, does not speak a single line until a half hour passes. However, this does not mean that no jokes are made at her expense in the meantime. (“I love… JACKIE CHAN!” a counselor greets her after he calls her “China,” not bothering to use her name in a moment that is supposed to be humorous. “Do you understand the words coming out of my mouth?”) When Zhenzhen finally does speak, she alternates between saying lines that could be easily prefaced with “Confucius says” or taken straight from the lips of a stereotypical lotus blossom (Shimizu, 2007): “My whole life,” she tells the lead (white) protagonist in a moment that is supposed to be romantic, “I have been searching for love. When I saw you on the bridge, I knew you were the one. If you feel the same way… kiss me now and we will be together forever.” The actress who plays Zhenzhen is 13 years old, and I could not help but wonder if the same would be asked of a white actress.

The one exception I found in the entire sample was Always Be My Maybe. This film, hailed as an example of how Asian/American representation is rising over the past couple of years, is praised for a reason. Always Be My Maybe doesn’t just have a cast of mostly Asian/American characters; it has a cast of well-rounded, complex, detail-rich Asian/American characters. All of them are treated with respect and empathy, and while there are comedic moments, the characters are not defined solely by these comedic moments. The film was filled with different relationships—not just familial ones or friendships, but also ones of a sexual and romantic nature. If a character gives advice, there is no mystic Confucius, but rather a person who has experienced life to its fullest and gained some wisdom in the process. Asian/American culture is imbued throughout the movie, and questions of race are dealt with, but in a fashion that feels like more like an aspect of a character’s humanity than a plot device. I did not have to code “Unknown” for any of the characters once, as I gained enough information about all the variables to code for them; this was the only program in which this was the case.

Download PDF

Download PDF