"Mimetics as Digital Culture"

About the AuthorJacklyn Heslop has her B.A from California State University, Stanislaus and is currently working on her M.A in English with a special emphasis on rhetoric and the teaching of writing at the same institution. She hopes to continue on to her PhD in order to continue her studies into memetics and/or writing centers. In addition to those already stated, her research interests are multimodal pedagogy, digital and visual rhetorics, and alternative forms of assessment (specs/contract grading). ContentsThe Enthymeme: Filling in Missing Pieces Cultural Inheritance: Darwin to Digital Rhetoric Meme Creation and Reproduction Enthymemes and Visual: Is There an Argument? |

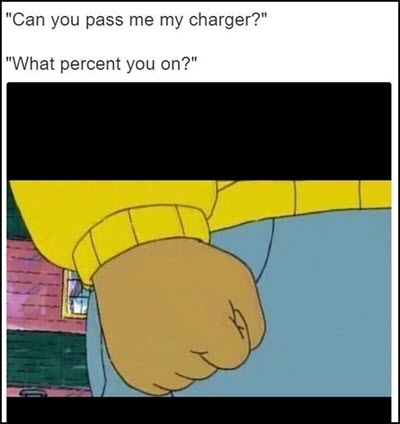

Enthymemes and Visual: Is There an Argument?Scholars are beginning to turn to the theory of the enthymeme in order to explain the implicit meaning drawn from images. Few have taken the theory further to begin arguing the validity of visual argument. Valerie Smith is adamant about the possibility of visual argumentation: “Aristotle’s conception [of the enthymeme] both explains how visual arguments are possible and helps us understand how they work” (115). Smith points out that the reductive view of the enthymeme as an incomplete argument not only limits its value but is a misinterpretation of Aristotle’s concept (116). She continues through an explanation of the differing abilities of the enthymeme: arguing in what is “probable” to allow the audience to “be convinced by these considerations but differences of opinion may remain,” to consider “ethical and emotional dimensions of argument,” and a strong connection between the message’s sender and receiver (117). The recognition of these qualities allows what would otherwise be ambiguous images to create meaning. Images, Smith recognizes, allow the viewer to infer meaning from what is familiar (120). Smith explains, “Within our cultural frameworks, we understand visual aspects of nonverbal communication to carry a limited and likely range of meanings”; for example, when a person is standing with his fist clenched and face red, onlookers would assume this person is angry (120). The enthymeme, as Aristotle proposes, allows the audience to complete the argument for themselves, which means the speaker must construct an argument that builds within it a system where the audience infers what is the “probable” conclusion given all the other information. The meme functions in the same manner. The community pulls an image and creates a probable interpretation, which is then used within each iteration to create the interpretive framework. Memetic internet media can create new codes for its culture, but often it digitizes communication that has already been established. For example, Smith exemplifies the clenched fist as a visual indication of anger, which is a universal symbol for feelings of rage. The “Arthur’s Fist” meme follows the same logic but uses a children’s cartoon from the 1990s to replicate this visual code to indicate frustration with trivial matters (knowyourmeme). Figure 5 reads as one speaker being frustrated because they cannot get back their property, the phone charger, because the borrower feels they need it more.5  Figure 5: "Can You Pass me my Charger?" This is a common problem in the digital age: as the younger generation relies on smartphones, people compare battery percentages to argue their need for a charger, whether the item is their property or another person’s. This image uses a well-known cultural code, clenched fist as anger, and creates a visual enthymeme for a very particular audience. The audience has to do most of the work in interpreting the message, but in explicating the implicit claims an argument can begin to form. While Smith argues the emotional appeals of visual enthymemes, her reference to ethos as a visual argument applies to memes, as the creation and dissemination of memetic media continually tries to prove assimilation to meme standard to present the media as a part of a collective rather than the individual. The content is original because the reference’s layers have been reformed, but adherence to the style of the meme signals to the audience that this meme belongs, so the creator must be a part of the community. Finally, she concludes by explaining that visual enthymemes function through the shared opinions of speaker and audience (Smith 121). She states, “Commonplaces, of course, are culture-specific grounds of potential agreement between speakers and audiences. Birdsell and Groarke suggest that visual commonplaces can argue just as verbal ones do” (Smith 121). 5. @SnipderDeuceZero “‘Can you pass me my charger?’ ‘What percent are you on?’” Twitter, 28 July 2016, 1:45 am, https://i.kym-cdn.com/photos/images/original/001/154/406/557.jpg. |

Download PDF

Download PDF