From Industry to Creativity: The Westinghouse Memorial and the Evolution of Pittsburgh

by Alicia Furlan | Xchanges 16.2, Fall 2021

Contents

20th Century Context: Cramped Spaces and a Smoky City

20th Century Context: Cramped Spaces and a Smoky City

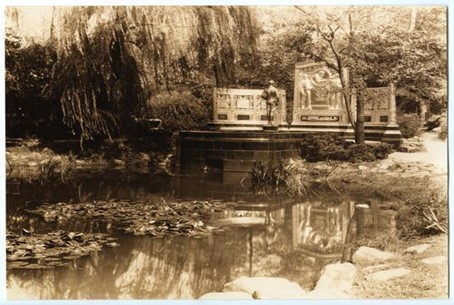

When the Westinghouse Memorial (Figure 2) was commissioned by the City Council in 1926, Pittsburgh’s identity was caught between two competing narratives, both defined by its status as a center of industry. On the one hand, the city was becoming the “Workshop of the World,” or “a city with the mission of promoting progress around the world” (Penna 52). Efforts of Pittsburgh’s business elite to promote their city to the nation tapped into this narrative, highlighting industry’s association with progress. Beginning in 1901, several articles began to be published in national journals and magazines hailing Pittsburgh’s industrial prowess (Penna 51). The first of these, “A Glimpse of Pittsburg” written in January 1901 by wealthy industrialist William L Scaife, celebrated the industrial smoke that coated the city: “The housetops and hillsides wear its colors, and numberless columns, like gigantic organ pipes, breathe forth graceful plumes of black and white. The city and its environs bear testimony to the sovereignty of Coal” (qtd. in Penna 51). To Scaife, the smoke was a symbol of the industrial power that caused him in “Pittsburg, a New Great City” to describe his beloved city as “a new thing under the sun… entrusted with a human purpose, . . . the utilization of natural forces to replace the enslavement of men” (qtd. in Penna, 51). Pittsburgh was to be considered and remembered as being part of a trailblazing and enduring tradition of progress and flourishing.

However, many of the human consequences of industrial progress constituted the very opposite of “flourishing.” The “Workshop” narrative peddled by Scaife and other elites ignored the effects that industry and unbridled growth were having on the living conditions of industry workers. But a report on Pittsburgh’s living conditions in the early 20th century forced elites to pay attention to a different narrative of their city. From 1907-1914, researchers conducted The Pittsburgh Survey, an investigation which uncovered a more negative image of the “workshop” and, to the dismay of the elites, revealed that residents lacked “the civic pride necessary to prevent environmental destruction and human degradation” (Penna 54). The writers of the survey found that the price of Pittsburgh’s rapid industrial growth was overcrowded, disease-ridden, and unclean mill towns where industry workers lived in squalor when they weren’t working. When they were working, it was often for 12 hours at a time: toiling day in and day out to push the engine of progress forward. For industry workers, the same smoke which Scaife celebrated created a “city of hills and mills and grime and smoke” where “it is difficult to keep clean under the most favorable conditions (Dinwiddie and Crowell, 95).

The Pittsburgh Survey also noted that the community spirit necessary to mobilize and address the unsanitary and overcrowded conditions was severely lacking among the exhausted and locally segregated population. In one section of the survey, social worker and later Secretary of Pittsburgh’s Civic Commission Allen Burns describes this hyper-localized concern, “…civic bodies organized under these local names have been interested primarily and mainly in the improvement of their own communities…councilmen chosen by wards throve through catering to local needs while indifferent or negligent to the weightier interests of the city as a whole.” (Burns 45). As Burns explains, Pittsburgh’s workers did not see themselves as being part of a broader city community, but rather as a collection of local neighborhoods who did not rely on or cooperate with each other. The consequences of this lack of cooperation and participation were often dire, as explained in the survey by its associate director Frank E. Wing, who describes how a lack of adequate water filtration caused typhoid to run rampant in several neighborhoods throughout the city for over 35 years. Despite such grim circumstances, the residents “only spasmodically and half-heartedly demanded the system of filtration which brought the delayed relief. In the meantime, those who could not afford to buy bottled water continued to drink filth” (Wing 66). In short, to the dismay of the elites, The Pittsburgh Survey revealed exhausted, sick, and disillusioned industry workers who did not identify with their city.

A remedy for the social ills driving this second, less flattering narrative of Pittsburgh required a strong city identity that transcended local concerns. After the shocking results of the survey, Pittsburgh’s business elites strengthened their attempts to bolster civic consciousness. Survey writer Robert A. Woods describes two gifts that elites hoped would create a greater city spirit:

In the absence of this community spirit, the individual acts of two persons stand out in notable relief. Before the close of the century, from the foremost absentee landlord and the foremost absentee capitalist came as gifts the two epoch-making improvements toward the finer public life of the city. Schenley Park and the Carnegie institutions located at its entrance form a civic center whose possibilities of civic influence are very great. (Woods 18)

Already in 1909, at the time Woods’ report was published, Pittsburgh’s elites had begun to consider the potential of sites such as parks and beautiful architectural spectacles to influence public identity and memory. However, as Woods goes on to explain, these sites did little to appeal to Pittsburgh’s industrial workers at the time. “…To the discerning eye, however, all this cluster of enlightened agencies points by contrast to the economic as well as moral conditions that prevail among the people in all the less favored sections of the city and in all the satellite industrial towns” (Woods 30). The contrast between the situations of wealthy employers and their impoverished workers was set in full view by the conspicuous existence of such institutions of higher learning and leisure that resided exclusively within the purview of the elites. In the survey, Woods goes onto explain how at the time, the sense of a “more generous and democratic sense of responsibility on the part of employers and the more prosperous classes generally” (Woods 30), had yet to reach Pittsburgh’s mass of unskilled laborers, who continued to feel as alienated as ever.

Later, in 1926, The Pittsburgh Chamber of Commerce launched The Pittsburgh Forward, in which they attempted to “sell Pittsburgh to Pittsburghers” (Penna 55) by equating the spirit of the city with the spirit of Pittsburgh’s industrial workers. When these efforts proved unsuccessful however, the chamber returned to what they knew and began once again to align the spirit of the city with the excellence of individual captains of industry such as “Carnegie, Frick, Jones, Heinz, and Westinghouse whose talents had helped to make the workshop a reality and to develop the natural resources which had made the workshop possible” (Penna 56). However, this more individualistic narrative was printed and pushed in a journal for Chamber of Commerce members and “It became the private domain of the city's business elite, contrary to the goals of the forward movement expressed only two years earlier.” (Penna 56). Therefore, this new narrative was similarly unsuccessful in bolstering civic support for improvements to living and environmental conditions, forcing industry workers to endure smoky working conditions well into the 1940s.

Download PDF

Download PDF