Examining Equity in Accessibility to Undergraduate Scientific Research

by Marion Olsen | Xchanges 16.2, Fall 2021

Introduction

Research can be defined as the methodical study or analysis of a question in order to gain a better understanding and derive new conclusions. Conducting research, therefore, is the backbone of science and drives advancement in all disciplines. Because of this, a scientist's career is often defined by the research they do and how they are able to better humanity’s understanding of the world around us. Just as research can advance a scientist’s career, for those undergraduate students wishing to become scientists, figuring out how to access research opportunities early on in a college education can help to introduce the individual to the scientific community at an earlier stage than their peers.

For science students, access to undergraduate research has a direct and significant impact on a student’s education. In terms of academic success, “results from a series of multiple regression analyses demonstrate that research involvement is associated with higher undergraduate GPA” (Sell, Naginey, & Stanton, 2018, p.19). Additionally, research has shown that students also benefit in the form of “the growth of self-confidence, independence of work and thought, and a sense of accomplishment” (Lopatto, 2010, p.27). The results of a national survey conducted by Landrum & Nelson (2002) found that generally, the benefits of undergraduate research for students falls into two major categories: interpersonal benefits and increases in overall technical skills. Interpersonal benefits include “teamwork, leadership and time-management skills, self-confidence, and interpersonal communication skills” while technical skills included a variety of discipline-specific “skills [that are] important for graduate school preparedness” (Landrum & Nelson, 2002, p. 16). Another study found that students also reported “increased career clarification [and a] better understanding of whether or not they wished to pursue a research career or attend graduate school” (Laursen, Seymour, & Hunter, 2012, p. 34). For students, these benefits are highly influential and have the ability to change the trajectory of their academic careers and resultingly, their lives.

The influential undergraduate research experience would be impossible without the key role of the research advisor. In fact, the research advisor often determines whether or not a student will gain access to research in the first place and can additionally act as a mentor for a student. Unfortunately, however, the priorities of the research university and the scientific community in general can negatively impact the research advisor/student relationship. It is important to note that research universities have historically prioritized the production of knowledge; the first U.S. universities that required faculty members to take part in research arose in the aftermath of the Civil War and were modeled after German research universities once they were seen to benefit Germany’s industry (Atkinson & Blanpied, 2008). The prioritization of the production of knowledge still pervades today as research professors are often required to publish scholarship and issues like tenure and research funding are often based on the relevancy of research to industry or university prestige (Atkinson & Blanpied, 2008). Additionally, strong communication skills are often valued by the scientific community due to the interdisciplinary nature of science and scientific writing. In her book The Forgotten Tribe: Scientists as Writers, Lisa Emerson (2016) argues that scientists are some of the most flexible communicators because unlike some disciplines, science requires collaboration and communication with a wide range of audiences, including industry, scientific peers from a variety of fields, and an assortment of different public audiences.

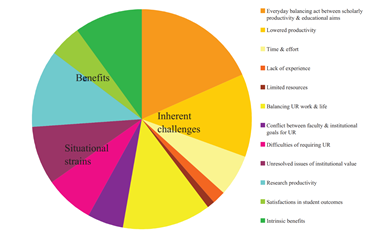

We can see the manifestation of these priorities and their effects on the research advisor-student relationship when examining how faculty regards research. One study found that for faculty, there are a variety of costs and benefits associated with undergraduate research that can be seen in Figure 1. Most benefits were emotional, including satisfaction and pride in student success, while some of the costs were more tangible including “inexperience and turnover of student lab workers” as well as “undergraduates’ slow pace and variable output sometimes compromis[ing] their productivity” (Laursen et al., 2012, p.35). Faculty also reported situational stresses associated with student research, specifically concerning institutional policies that make research a requirement for graduation. Faculty reported that they “felt pressured to accept ‘weaker’ students” when research was required (Laursen et al., 2012, p.36). This suggests that professors and students have strikingly different views about student research: for students, research is the key to success; for professors, research is, at best, emotionally rewarding and at worst a burden. This sets up a polarizing power dynamic that influences how students and professors engage in discourse and poses some challenges for the scientific community as to what conducting student research should look like.

The priorities of the research university and this polarizing power dynamic unfortunately has the potential to affect the equity of student access to undergraduate research. Equity can be defined as equality of opportunity and is recognized by the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) as one of the core principles of what the organization calls “Inclusive Excellence.” It was my belief that despite this emphasis on equity and inclusiveness, access to undergraduate research at my university (a member of the AAC&U) had the potential to be inequitable. Because the research advisor has to worry about issues of research funding, publication quotas, and how their research could impact their standing within the university, it is likely that research advisors actively search for students who could help them achieve these goals (e.g. “stronger” students). This could be detrimental to students who are reliant on the research advisor to allow them access into the research space because what counts as “strength” is likely influenced by the research advisor’s implicit bias.

While there are many studies looking at the benefits of student research for both faculty and students (e.g. Landrum & Nelson, Laursen et. al., Lopatto & Sell et. al., ), there is a gap in literature in regard to equity in accessibility to undergraduate scientific research opportunities (accessibility in this context being the opportunity to partake in undergraduate scientific research). With the understanding that student research is a valuable experience for students and a gateway into the scientific community and the context of what the research university values, I will be looking at how my university, as a school that advertises an emphasis on undergraduate research, influences how students can access research and how professors provide opportunities for student research.

Download PDF

Download PDF