Examining the Effectiveness of a Peer Writing Coaching Model

by Jennifer Wilhite | Xchanges 17.1, Spring 2022

Methods

This IRB-approved research study focused on the following questions in regard to the writing experiences of graduate students at my university:

- Does writing manifest as a barrier to expected completion of graduate programs for women who are returning to school after pursuing a career or personal path?

- What kinds of graduate-level writing support do women returning to the university find most helpful/least helpful, and why?

- What steps can universities take to design writing initiatives that target the specific needs of women entering graduate programs after time pursuing industry and life goals?

Disciplinary histories of Rhet-Comp are often intertwined with the history of shifting labor conditions in the university. Where one places the beginning of the field in the academy depends on who you ask (e.g., Bazerman, 2005; Brereton, 1995; Murphy, 2012), but wherever you choose to start, you will also find academics discussing their labor conditions. As the 1970s and 80s marshalled an increase in graduate programs in Rhet-Comp, so too did conversation about Rhet-Comp’s place in the academy, especially as it relates to Literature. These discussions, perhaps best summarized in Maxine Hairston’s (1985) emphatic CCCC’s address, offer a painful picture of labor standards for writing instructors. These accounts focus on common demands also highlighted in the labor movement: working for dignity and respect on the job.

I explored these questions in the fall of 2020 and spring of 2021 by interviewing and working with graduate students in various stages of their course work, thesis, or dissertation. I recruited potential participants from the university’s graduate school sponsored programs including writing retreats and writing groups. Per COVID-19 protocols (2020-2021), all writing retreats and writing groups met online and I recruited participants by volunteering during writing retreats to assist retreat participants with any sort of writing support they desired. When participants reached out to me, I assisted them in a variety of writing tasks from checking basic grammar to discussing structure to designing next steps. If the participants asked about my project, I explained my work and invited them to talk to me about their writing experiences in a loosely structured interview.

I narrowed the scope of this study after working with a variety of graduate students over the course of three years. During university-sponsored writing retreats, I met with an assortment of masters and doctoral students whose ages ranged from 20 to 60 and included men and women. During retreats I worked with students on sections of their projects; after retreats, I continued to work with students who wanted further writing support. The more I worked with graduate students, the more I realized the majority of those who sought my help were women returning to school after time away from the academy and that their support needs and wants were different from those students who continued from their undergrad into their graduate studies without interruption. The intersections of their multiple positionalities can create disruptions in their academic trajectories and can potentially completely derail their degree plans. So, while I continued to work with all graduate students who sought me out, I decided to focus my research on the needs of women returning to school.

In order to better understand their experiences and gain insights into what supports could benefit all graduate writers, I conducted interviews with twelve participants. I used participant-selected pseudonyms to differentiate participants and protect their identity; all participants identified as women. Eight of the women participated as interview-only (Brisa Solaris, Little Red Riding Hood (LRRH), Muktaa, Maria Martinez, Catherine Acosta, Maria Joseph, Mena, and Yun Lin) and we enjoyed a loosely structured interview wherein I encourage them to speak freely about the good, bad, ugly, and sublime writing experiences they had and were having through their academic career. These women’s graduate experiences ranged from a few semesters into their program to women polishing the last edits of their dissertation.

In addition to the interview-only participants, I worked closely on writing projects with four women, two in STEM (Violet UV and Jessica Watkins) and two in humanities (Nora DeJohn and Bernadette Volkov), for one (Bernadette Volkov and Violet UV) or two (Jessica Watkins and Nora DeJohn) semesters. I interviewed participants before we began working on their projects. After the intake interview, we met once a week for feedback on their writing, review their progress, talk about their work and set goals for the next meeting. I listened to them talk about their challenges and successes and observed their project progresses and how they coped with their writing demands. We also conducted an exit/reflective interview. Working with these women allowed me to see first-hand the struggles that are inherent in graduate programs and those that are unique to my participants. I knew if various supports were effective by asking participants what kinds and elements of writing supports (including but not limited to the support I provided) productively assist them in finishing their projects and degrees and by observing their progress based on their goals.

The following questions were included in the loosely structured interview:

- What is your first language? What other languages are you semi-proficient or fluent in?

- What is your field of study?

- How long have you been in your graduate program? How many years total do you anticipate spending in your graduate program?

- When and where and what was your last writing class?

- What are the writing expectations of your program?

- Are you working on a writing project now?

- What, if any, writing supports have you used?

- What kind of supports would you be willing to use?

- Who/where do you go for help if you need writing assistance? What do you enjoy about this support? What are some of the challenges with this support?

- What campus writing resources do you consider reliable? What have they done to earn your trust?

- Is there any campus writing resource you consider unreliable? Why? What happened?

- Have you ever had a really positive writing experience? What made that experience really positive? What would have made it even better?

- If you have ever had challenging experiences with writing? Can you talk about that? What did help? What would have helped?

- If you were to design a writing support program for those that follow you, what elements would you consider essential?

This article focuses on questions that explore the writing experiences including struggles as well as triumphs and aims to determine if writing manifests as a barrier to degree completion and what universities could do to support graduate writers more effectively.

Analytic Framework

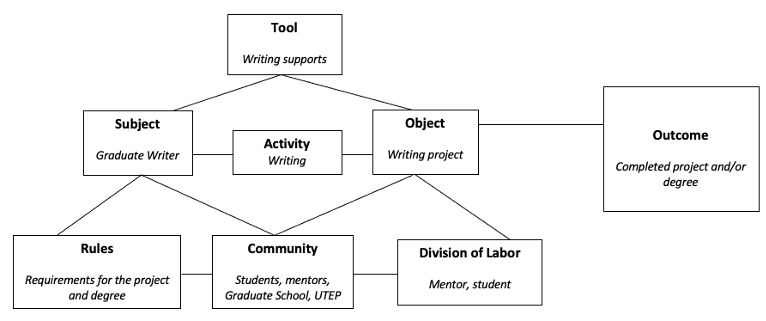

In order to analyze this data, I used an analytic framework combining action research, Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT), and Feminist Standpoint Theory (FST). Action research embraces both theory building and practical application by identifying a problem and seeking a solution through collaboration between researcher and participant (Acosta & Goltz, 2014; Baum et al., 2006; Waterman et al., 2001). CHAT posits that human society consists of many inter- and codependent activity systems that utilize tools to obtain outcomes (Feryok, 2012; Hasan & Kazlauska, 2014; Hashim & Jones, 2007; Hold & Morris, 1993; Lundell & Beach, 2003; Koschmann, 1998).

Exploring the lives of graduate writers in terms of CHAT “fosters a more complex and comprehensive understanding of the features which impact on the effectiveness of a learning situation” (Scanlon & Issroff, 2005, p. 438). CHAT terminology enables me to situate the relationships between the university, graduate students, mentors and advisors, Graduate School/other programs with writing supports, and the different writing supports found across campus. I also use CHAT as a framework to map the history and context of the activity systems of graduate students’ experiences wherein they write (Hasan & Kazlauska, 2014; Lundell & Beach, 2003). CHAT seeks to understand the cultural-historical factors that give birth to and sustain an activity system and FST asks that as many perspectives as possible be considered. FST also recognizes that writing supports must be made available to, but not forced on, all graduate students.

Project participants (participants with whom I worked beyond the interview for a semester or longer) met with me once a week, with deviations per their schedule or needs. CHAT and FST frameworks deepened the action research approach by keeping me mindful of the importance of careful listening and being cognizant of participants’ competing activity systems. As we worked together, I would suggest supports (for example: genre analysis, editing, and goal setting) and the participant would agree to or amend the idea. The support would be attempted and then reflected upon the next meeting then retooled or continued. As we worked, I talked to the participant about their challenges and successes and what supports seemed to help move their project forward, what supports merited repeating, and what further supports they would like to try.

When working with students initially (prior to making this a formal study), I met with an assortment of masters and doctoral students whose ages ranged from 20 to 59 and included men and women. The more I worked with graduate students at writing retreats and in my writing group, the more I realized those who sought help tended to be women returning to school after time away from the academy and that their support needs and wants were different from those students who had continued from their undergrad into their graduate studies without interruption. So, while I continued to work with all graduate students who sought me out, I decided to focus on the needs of women returning to school. Each participant is a mother of a child or children of different ages, and each is pursuing a degree in a different field. This diverse group of mothers along with the four graduate projects and eight interviews allowed me access to a rich set of graduate writing experiences.

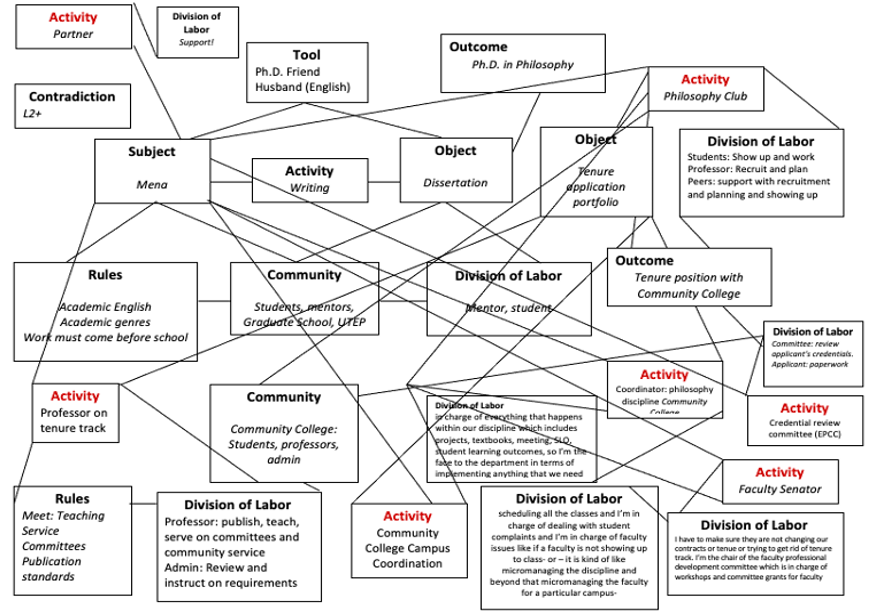

To analyze each interview, I created a CHAT map for each participant. Kain and Wardle (2019) write that activity theory can help the researcher “more fully understand the ‘context’ of a community and its tools” through the terminology and “by providing a diagram outlining the important elements and their relationships” (p. 5). I created layers of activity systems for each participant. Figure 2 is representative of a writing activity system. However, every graduate student has more activity systems than just their writing projects, so, utilizing the information from the interviews and the CHAT concept that each participant has multiple activity systems, the researcher layered the writing activity system with other systems the interviewee spoke of (family, work, friends, pandemic issues, health, etc.).

Figure 3 is an example of Mena’s complex activity systems. She is pursuing a doctoral degree in philosophy as well as seeking tenure in a local community college. Her activity systems overlap and can compete for Mena’s attention; however, she has found affordances in her academic communities that support her writing and her progress towards her desired outcomes.

After conducting and transcribing all interviews, I coded them utilizing CHAT terms (Subject, Tools, Contradictions, Community, Rules, Division of Labor, Objects, and Outcomes). The CHAT charts and themes from the researcher’s notes were analyzed looking for the specific kinds of tools that the participants used and why/how those tools either worked or failed. Tool evaluation took into consideration what composition tasks they were supposed to support and how the tools the participants responded to change over time and how they might change in the future. Although not originally intended, the CHAT maps also revealed affordances as participants found creative approaches to support their education and balance their other responsibilities.

I also tracked themes that repeated in all or many of the graduate writers’ experiences. These themes include challenges, effective and not effective supports, successes, positive writing experiences, negative writing experiences, advisor relationships, descriptions of desired supports, etc. I analyzed the interviews and field notes again, looking specifically for answers to the study’s research questions. The CHAT and themes also ascertain what kinds of graduate-level writing supports women returning to the academy find most helpful/least helpful.

As I worked with each participant, I (sharing my observations with them at specific points) added elements and activity systems to the participant’s chart as they became apparent and manifested in the participant’s conversations and (re)scheduled sessions. I asked questions but tried not to be intrusive. If other activity systems interfered with writing, I noted these systems. If writing interfered with other systems or slowed down program progress, I especially noted these issues. I also tracked themes that repeated in graduate writers’ experiences across projects and interviews. These themes include challenges, effective and not effective supports, successes, positive writing experiences, negative writing experiences, advisor relationships, etc. The participant’s CHAT chart was completed with the final exit interview. I analyzed CHAT charts and themes from my notes looking for the specific kinds of tools that the participants used and why/how those tools either worked or failed. FST reminds the researcher that the authentic voice of the participant is the most significant data in the research and is not to be coerced or misrepresented. I offered all participants an opportunity to read the transcripts of their interviews, read the study findings, and respond to both in writing.

Download PDF

Download PDF