Examining the Effectiveness of a Peer Writing Coaching Model

by Jennifer Wilhite | Xchanges 17.1, Spring 2022

Abstract

With the growth in scholarly and practical interest in providing improved support for graduate student writing, limited work remains exploring the experiences of older women returning to graduate study after supporting family or a previous career. Graduate writing support interventions have not been adjusted to help students returning to the academy who may have found that it has changed drastically and need additional or qualitatively different support than is currently offered for those students who have moved directly from undergraduate study into graduate school. This article is based on a three year study involving observations, interviews, and active peer mentoring with women returning to graduate education and needing additional writing support in order to succeed in their respective fields. Using cultural historical activity theory (CHAT) and feminist standpoint theory (FST) to analyze the results, this research suggests that peer mentoring can be an effective mode of peer support for this particular group of students. This article closes with suggestions for the implementation of full time peer mentoring support for graduate writers in higher education.

Introduction

Academic writing can be defined as the modality the academy has selected to measure learning and determine the quality of knowledge made. Writing then is vital to graduate research projects because it is the medium through which students present their findings. Since it is projects like masters’ theses, doctoral dissertations, journal articles, and other publications whereby peers, professors, and professionals rank the merit of students’ conclusions, it is students’ writing that can potentially propel them into an expert status or flatline their academic trajectory. Writing for the field is how nascent academics develop their professional identity. Their research in masters and doctoral programs is the foundation upon which the student builds their expert status; thus, the stakes are high and writing challenges can manifest as barriers to degree completion that disrupt career trajectories.

One of the challenges of the graduate student is being seen as an expert. To gain legitimacy, scholars identify and fill scholarship gaps in the important conversations of their discipline. Graduate students embody or question their field’s “traditions, practices, and values” (Casanave, 2002, p. 23) through knowledge claims in genres that present their theoretical approaches and thus craft their academic identity in opposition or alignment with established experts (Aitchison, 2014; Paré, 2014). As they publish their new knowledge, an academic begins to craft their identity as an expert (Kim & Wolke, 2020). It is their published writing that legitimizes a scholar’s expert identity and propels the successful writer into their academic community as someone who speaks with authority (Casanave, 2002). This authority gives academics greater access to professional opportunities. In knowledge-based careers “where the primary product is making and distributions of symbols” or texts, “the activity system is centrally organized around written documents” (Bazerman, 2004, p. 319). Those who write a successful thesis, dissertation, and/or publication are more likely to be further published and cited and gain employment; thus, the university, a preparatory training ground, centers writing to give graduate students opportunities to become professionals (Brooks-Gillies et al., 2020).

Historically, providing postsecondary writing support became popular in the US during the 1970s to address increasingly diverse demographics of people (i.e., by class, nationality, race, gender) that were entering the academy in higher rates and did not have the academic English skills US academic traditions upheld and still uphold (Brooks-Gillies et al., 2020; Caplan, 2020). The classes were often titled as “remedial” courses; thus, seeking assistance with writing might signal inadequacies in the writer, not the academy (Russell, 2013; Hjortshoj, 2010). Unfortunately, when graduate students need writing support, they may believe that they will lose credibility in the eyes of their professors, peers, and advisors if they admit to writing weaknesses and may feel stigmatized if they need assistance with “grammar rules or punctuation conventions simply because of the length of time since they have received writing instruction” (Thomas et al., 2014, p. 73). It can be difficult for someone who is trying to position themselves as a professional to admit they have forgotten how to cite in APA or that they are struggling with the genres that graduate students must learn to become legitimized in the academy because admitting weaknesses can feel like being exposed as being subpar and incapable of completing a degree much less succeed in a career (LaFrance & Corbett, 2020; Li, 2014).

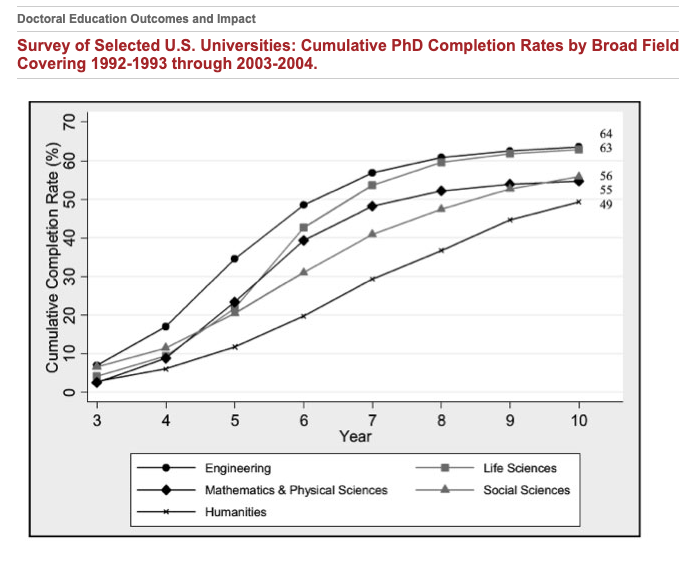

Overall graduate school attrition rates in the U.S. are estimated to be around 40% with higher dropout rates occurring in the humanities and social sciences and higher retention rates in lab sciences (Council of Graduate Schools, 2015; Holmes et al., 2018). Relatedly, the graph in Figure 1 addresses completion rates in Ph.D. programs at selected US universities. Even students who persist into the later phases of their programs are at risk of dropping out before completing their degrees (Wolfsberger, 2014). In fact, research indicates that the longer a student is in a graduate program, the more likely they are to drop out (Caruth, 2015; Council of Graduate Schools, 2015; Holmes et al., 2018), with the highest rates of attrition at the all-but-dissertation (ABD) stage (Lundell & Beach, 2003). Because graduate writing is the primary modality in which graduate programs evaluate the depth of learning and quality of new knowledge, writing can manifest as a barrier to successful and timely degree completion and post-degree employment. Writing challenges of all graduate students can include being unfamiliar with the genres of academic writing, writing in a nonnative language, years away from school, family responsibilities, social isolation, employment demands, and other visible and invisible issues (Caplan, 2020; Kim & Wolke, 2020).

We can see the manifestations of universities’ priorities and their effects on graduate matriculation and attrition rates in the range of writing supports universities design for their students, which include university writing center tutors, writing camps, writing classes, and writing groups. Universities like Rutgers offer focused graduate writing courses and widely accessible sources like Consortium on Graduate Communication offer all graduate students and their professors a space to address writing challenges. Professors can be expected to guide students in learning content, planning projects, carrying out research, and in the many types of writing that pervade graduate programs; these people are the most important factor in the student’s academic success (Kim, 2020; Jones, 2016; Thomas et al., 2014). However, professors, advisors, directors, whatever the titles may be, carry large workloads and may not always be available to students and sometimes students are nervous about submitting a draft to their advisor because the draft may need considerable revision and they worry about frustrating their advisor or appearing inadequate (Brooks-Gillies et al., 2020; Henderson & Cook, 2020).

Universities frequently provide support systems for writers at both the undergraduate and graduate levels in writing centers and are more often tailoring options to meet graduate students’ needs (Fredrick et al., 2020; Holmes et al., 2018; Pinkert, 2020; Tauber, 2016). However, given the “high-stakes and highly-technical” nature of graduate writing, the “disciplinary expertise requires a level of writing and disciplinary knowledge that both GWC [Graduate Writing Center] consultants and graduate students sometimes lack” (Summers, 2016, p. 118). One writing support universities frequently host is the writing camp or retreat. Retreats and camps are frequently sponsored by university writing centers, libraries, or graduate schools and sometimes by specific departments for their own students (Busl et al., 2020; Douglas, 2020; Knowles & Grant, 2014; Li, 2014; Lundell & Beach, 2003; Murry, 2014; Pinkert, 2020; Russell, 2013).

Peer support can take the form of peer mentoring wherein more advanced peers work with beginners, or less experienced writers. When setting out on writing projects, less experienced or beginning writers can feel anxiety that inhibits even starting the project; however, working with those “who are more advanced in their research careers” (Mewburn et al., 2014, p. 226) can create a safe space to ask questions, look at model texts, and experiment. Research shows that structured peer mentoring is an invaluable resource for both mentor and mentee (Simpson et al., 2020; Maher et al., 2006). A popular form of peer writing support is the writing group. “Writing group” is a broad term that generally refers to a deliberate situation where at least three people “come together to work on their writing in a sustained way” (Aitchison & Guerin, 2014b, p. 7) and can include providing instruction or feedback, talking about writing, motivating reluctant writers, increasing confidence in abilities, and providing social support in general (Aitchison, 2014; Brooks-Gillies et al., 2020; Kim & Wolke, 2020).

While there are many studies that explore the experiences of graduate writers (Aitchison, 2009, 2014; Aitchison & Guerin, 2014a; Ali & Coate, 2012; Bair & Mader, 2013; Bosanquet et al., 2014; Brooks-Gillies et al., 2020; Cotterall, 2011; Gernatt & Coberly-Hold, 2019), there is not much research conducted specifically on the experience of older women returning to the academy; there is even less specific research aimed at those women whose intersections also include studying in their second or third (or more) language. Returning women, who are older than those who had linear academic trajectories, may find the academy has changed drastically since they were students and thus, they may have a harder time adjusting to the rigors, demands, and expectations. They also often have accumulated many roles to which they must attend while attending to their degrees and may sometimes have a hard time differentiating criticism of performance from criticism of person (Casanave, 2010; Fredrick et al., 2020; Kirsch, 1993).

It is important, as the populations of women returning to the academy are not insubstantial and those numbers only promise to grow, to design research that examines how women in complex situations “address and represent audiences, and how they negotiate and establish their authority in written discourse” (Kirsch, 1993, p. xvii) and what supports may assist them to the completion of their degrees. With the understanding that all graduate students are valuable, I will be looking at how a peer writing coach supports older women returning to the academy because research that explores their concerns and experiences can provide starting points for designing university sponsored writing supports that could potentially benefit all graduate students.

Context

The university in this study is located in the Southwest US and is a public university with 21,117 students, 3,762 of whom are graduate students. Most of the over 100 masters’ programs require a thesis, and some require publications; the 22 Ph.D. programs mandate dissertations and require students to participate in the publication process before the degree will be awarded. Women make up 56% of the entire student body. Most of my university’s graduate students are between the ages of 25-29; however, there is a substantial number of students in the 30+ categories, including 1,591 between the ages of 30-49 and 209 who are over 50.

Download PDF

Download PDF