"Digital Invention: A Repository of Online Resources for College Composition Instruction"

|

About the AuthorMary K. Stewart is a PhD candidate in the School of Education at UC Davis, where she is pursuing an emphasis in Language, Literacy, and Culture, and a designated emphasis in Writing, Rhetoric, and Composition Studies. Her dissertation research focuses on the ways first-year composition instructors design collaborative activities (namely small group discussion and peer review) in computer-assisted, hybrid, and online environments. Find her website at MaryKStewart.com Contents |

MethodsMost students and teachers do not have the time to sift through every university's online resources, yet there is a plethora of high-quality material available, and, as argued on the Invention and Digital Literacy page, incorporating online resources into the curriculum can simultaneously teach multiple methods invention and promote digital literacy. The Locating Online Invention Resources and Selecting Online Invention Resources describe my process for locating and selecting the online invention resources on this website. Selecting Writing Center WebsitesI narrowed my search for online invention resources to university writing center websites because (a) I trust that these sites offer reliable resources grounded in composition pedagogy, and (b) narrowing in this way allows me to comment on resources officially sanctioned by the academy. However, it should be noted that non-university resources exist, such as Tom March’s Thesis Builder or online mapping tools like Mind Meister, Bubble.us, and Mindomo. To select the writing center websites (more commonly referred to as Online Writing Labs, or OWLs), I began with US News and World Report’s best “writing in the disciplines” colleges. The 17 colleges on the list prioritize the writing process “at all levels of instruction and across the curriculum” (US News & World Report). All of the 17 have a website that can be categorized as one of Jane Lasarenko’s (1996) three categories of OWLs:

For this project, I focused on the third type of OWL, narrowing my list to seven writing center websites that have distinct sections devoted to online resources: 1. Purdue University I also added two colleges to my list that were frequently referenced by the other universities: 8. University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill Finally, upon the recommendation of a writing instructor at my institution, I added: To better understand the writing centers’ resources, I emailed each center’s director. Dr. Vicki Russell (Duke University), Dr. Karen Gocsik (Dartmouth University), and Dr. Linda Bergmann (Purdue University) responded with the following information:

These directors’ responses indicate that they are actively promoting faculty and student use of the online materials. Further, while there is not a generalizable methodology for updating the resources, they are monitored and updated on at least an annual basis. A great deal of research and thought goes into determining what information will be available online and how that information will be presented. The directors’ responses also indicate that the resources available online are often viewed as handouts, as electronic equivalents to paper documents used in class or in the writing center. Consequently, the resources are almost all text-based and many maintain their effectiveness when printed. However, while existing resources may not be very media rich, exposing students to a digital experience instead of offering a paper (or verbal) explanation of invention promotes digital literacy in the following ways:

Because the databases are associated with universities, students can contextualize the information and associate it with a specific community. Selecting Online Invention ResourcesFrom the 10 writing center websites identified, I selected the online invention resources that were the most clear, most intuitive, and most visually engaging. Because I was looking at respected university websites, I assumed that the resources were equally grounded in contemporary composition pedagogy; consequently, I focused my selection process on clarity, intuition, and visual engagement because human-computer interaction and usability research, as well as digital design theory, tell us that these characteristics benefit a user’s experience with a website and thus increase online reading comprehension. That said, because clarity, intuition, and visual engagement are somewhat subjective characteristics, I included alternative resources on the Teaching Invention pages so the instructor can select the best resource for her students. This flexibility is crucial to teaching invention and to promoting digital literacy because invention is a varied and individualized process, as are most digital skills. Selecting ResourcesMy process for selecting and categorizing the resources on this website was as follows:

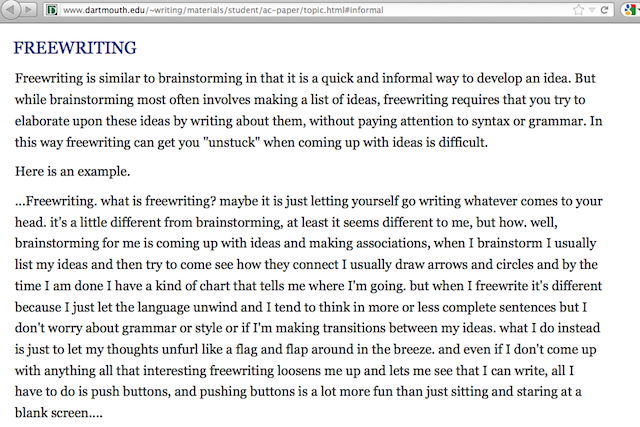

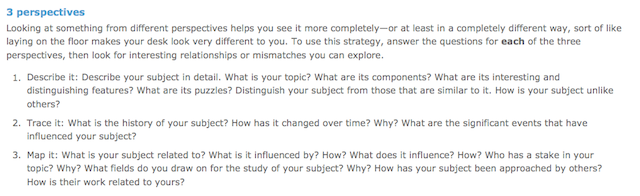

Creating Teaching Invention and Practicing InventionOnce the resources were selected, I created the tables you see on Teaching Invention. These tables list all of the invention resources I deemed clear, intuitive, and visually engaging, and include brief explanations of the resources. I also created the Practicing Invention pages, which provide links to both the “definition” resources in the explanatory part of the page, and to the “activity” resources in the suggested activities for practicing the invention strategies part of the page. Using some Writing Center Websites More than OthersYou will notice that not all ten of the writing centers I identified for this project are referenced on Practicing Invention, and I link to some writing centers more frequently than others. Part of this is because some sites simply have more information. Colorado State University, for example, has detailed resources for classical invention (especially when it comes to audience and purpose), but they don't mention many prewriting or tagmemic invention strategies. UNC-Chapel Hill, on the other hand, lists 13 different invention strategies; although their explanations are less rigorous, I link to their page more often than I link to CSU. Other universities, like UW-Madison and Hamilton College, have great writing resources, but nothing specific to invention. University of Wisconsin-Madison in particular has a very user-friendly site, but most of their information is divided by paper-type. If I were to create a similar project for writing across the disciplines, I'd rely more heavily on UW-Madison. Examples of “Clear, Intuitive, and Visually Engaging”Brown University's “11 Useful Things to Do when Writing a Paper” is a good example of a resource that is not very clear or intuitive. Compare the third item listed on the first screenshot below with the second screenshot. Dartmouth's explanation of freewriting is more detailed and gives an example. It's also easier to access—if you go to Brown's site, you have to scroll down to the bottom of the page just to find the list of 11 things, and the activity is not named. On Dartmouth's site, there's a large heading and you only have to scroll down a few lines to find it.   Like Dartmouth, Chapel Hill is a good example of a site that is clear, intuitive, and visually engaging. As the below screenshot demonstrates, their site has a comprehensive explanation of the invention strategy, can be accessed directly without the need to scroll, and has a clear title, plenty of white space, and easy-to-read bullet points.  On the other hand, Harvard University's How to Read an Assignment is not visually engaging. While the page has some great content, the small black text that fills up every available inch of the white background is difficult to read.  |