Cameraphone Composition: Documentary Filmmaking as Civic-Rhetorical Action in First-Year Composition

by Jacob D. Richter | Xchanges 16.1, Spring 2021

Contents

The Retold Histories of Clemson

The Process: Making Documentary Videos in the FYC Classroom

The Retold Histories of Clemson: Three Documentary Films

Behind the Scenes”: Access, Accessibility, & Audiences

Appendix A: Assignment Prompt for The Retold Histories of Clemson Project

"Behind the Scenes”: Access, Accessibility, & Audiences

Among the obstacles to the creation of a multimedia work like The Retold Histories of Clemson was the question of how to properly design an environment in which students are equipped to create and invent with technological tools, all the while avoiding the feelings of anguish and dread that can often accompany trying something new. In a multimedia project, students must learn that temporary setbacks do not constitute failure, but rather are simply a part of the invention process, especially when new technological practices are being mastered.

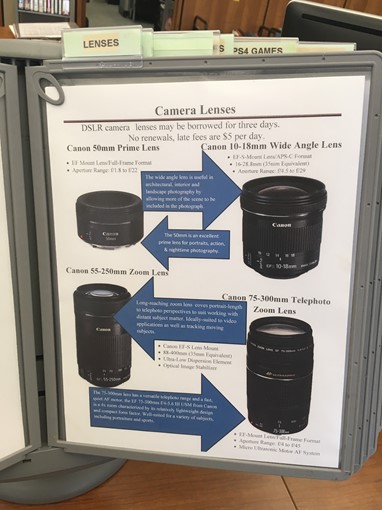

Many campus libraries feature technological and multimedia rental options for students (See Fig. 4). Technological literacy in the development of The Retold Histories of Clemson was supplemented by the availability of librarians to come in and teach our students a popular video-editing application that students were able to make use of on public library computers, on student-owned laptop computers, and even on their mobile smartphones. Few, if any, of the students had much experience recording video, and only one student reported any experience editing films, which was limited to working on a smartphone to edit family videos for popular video-sharing forums such as YouTube and TikTok.

In a single session, a technological resource librarian was able to come to our classroom and demonstrate a video editing application with students in a hands-on, active learning session. Students walked into class that day with almost no video editing experience, and left an hour later with a fully-formed video file on their computers, complete with music, scene cuts, footage edits, credits, and a working knowledge of how to further supplement their knowledge of the film editing program. Mostly, many left class with confidence, with a demystified outlook concerning the practical process of editing footage and moving through the invention process using the audio-visual tools at their disposal. When working with audio-visual tools, clear guidelines for production as well as a clearly stated articulation of the goals of the project can prove paramount to ensuring student success. Similarly, students must be allowed time and room to experiment, to play, and finally to explore in directions they find interesting.

What was vital for the success of the project, and I argue for all multimodal projects in higher education classrooms, was the assembling of a group of individuals willing to listen, support, and assist each other in the various challenges that inevitably pop up when working with unfamiliar technologies, formats, file types, and software applications. To sustain the filmmaking process from conception and script writing all the way through filming, editing, refining, uploading, and distributing, students need to be allotted the time and space required to learn from mistakes and to adjust their process accordingly. In cases such as these, it is incumbent upon the course instructor not necessarily to provide the resources, the attention, and the technological expertise needed to assemble a full 3-minute short film, but rather to design situations in which students are put into contact with community members who are equipped with these specialized skills, competencies, and proficiencies. While I may not be an expert filmmaker, I did make myself available to my students beyond set-aside office hours allotments, including walking one student group to the library to show them a room with an available greenscreen for their film as well as helping one group dealing with wind noise in their video to locate, install, and properly utilize a lapel microphone.

One challenge we faced when making The Retold Histories of Clemson occurred because, even at a large campus, there was a scarcity of video cameras available for student use (See Fig. 4). The degree of scarcity for available technological tools was partially unforeseen, due primarily to the timing of the project in the final weeks of the semester, a time ripe for final multimedia projects in other courses and departments as well as for one of the campus’s most popular courses, FYC. As an alternative, in an era in which 81% of Americans own some version of a smartphone according to the PEW Research Center, mobile software applications become a tangible possibility for the rhetoric and composition classroom (PEW). This number reaches 96% of Americans within the age 16-29 demographic, further supporting the idea that multimodal initiatives might benefit from incorporating some level of smartphone use in the curriculum.

Instructors cannot, of course, ever assume access to devices such as smartphones to be a given, as the technological access divide is well and alive in the United States and beyond (Anderson and Kumar, 2019; Banks, 2013; Losh, 2014). Keeping this in mind, however, we must also consider the ease of use of many technological applications, the ready availability of computers and free software application on many campuses, and finally the inexpensiveness of production, reproduction, and distribution within digital networks. Students do not need to use industry grade software when working multimodally. In fact, free, inexpensive, or open-source tools such as Canva, Filmr, Pitivi, Openshot, Lightworks, and Adobe Spark Video are often well-suited for student use, as these tools will likely be available off campus and beyond the student’s official academic curriculum, increasing the likelihood of that student to engage in multimodal creation or activism outside the confines of particular projects. Smartphones, then, are best seen in the rhetoric classroom as an asset, but not an expectation, for multimodal invention. Access to smartphones equipped with the complex, evolving, and expensive material infrastructures needed to produce a short film should not be assumed. When smartphones with these capacities happen to be present, however, they can be an asset to the classroom workflow.

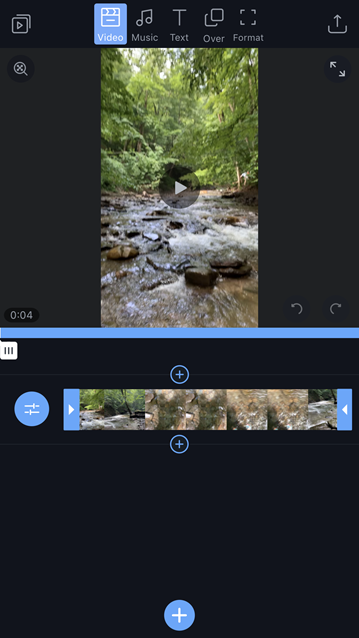

In the case of The Retold Histories of Clemson, a number of groups decided that a smartphone-enabled production process would benefit them, including in the ease of use, the simplicity of video uploading, and the ready availability of free, inexpensive, or open-source applications such as the Filmr screenshot showcased in Fig. 5. These students, equipped with tools that often are available, but which are not systemically relied upon or necessary for full success in the course, evolved over the course of our roughly one-month unit into cameraphone composers who assemble a coalition of publics, engage multimedia production, and author histories that value our shared communities in ways that are public, inclusive, and dedicated to righting social injustices in small but important ways.

A second challenge we faced when assembling The Retold Histories of Clemson was the accessibility and usability of technological tools by every student in each of the courses. Students work with technologies in different ways, some of which can be predicted at the start of a multimedia project, and some which must be worked out as the project progresses and as challenges arise. The intersections between technology use in the classroom and opportunities for greatly expanded accessibility are explored by a number of scholars. Many have begun to make the case that instructors should consider accessibility and inclusivity prior to or wholly within any initiative that engages technology and multimedia, rather than doing so retroactively in a way that can ostracize students and fail to recognize the full scope of what accessible project design entails (Vie, 2018; Dolmage et al., 2020).

Scholars writing in rhetoric and composition (Dolmage, 2017; Dunn & Dunn De Mers, 2002; Yergeau et al., 2013) and in technical and professional communication (Meloncon, 2014; Palmeri, 2006; Ray & Ray, 1998) have proposed strategies to foreground attention to disability when we design and implement projects that use multimodal technologies. Disability is a vital consideration when designing pedagogies that use digital tools, and it is incumbent upon every instructor to consider ways in which accessibility and usability can exclude students from full participation. When considering multimodal assignments, accessible project design must consider accessibility holistically from the project’s inception. Ultimately, occasions can be designed which maximize each student’s strengths and ways of participating in the construction of a film, a video, or a multimedia production. In the case of The Retold Histories of Clemson, we devised strategies to ensure each student contributed their best work and was able to engage the goals of the project with equal vigor, contribution, and opportunity. For instance, a student who is either unable or uninterested in recording the video voiceover has additional contribution opportunities that include script writing, location and selection of featured images, video editing, and coordinating the camera and microphone rental process.

A final challenge that this project required our course to navigate relates to the different levels of interest students had in pursuing a project that forced many of them to confront questions of power, privilege, and identity. While many students participating in this project embraced the challenge of pluralizing narratives and uncovering alternative ways to view “conventional” histories, some students were less comfortable confronting difficult and violent histories within their local campus communities. In the United States, anti-racist and social justice work are hardly uncontroversial, especially in settings and institutions that privilege traditional perspectives invested in maintaining status-quo narratives. Commitments to social justice, equity, and advocacy are hardly universal, and projects that engage these ambitions must grapple with a multitude of perspectives related to how local histories, especially those concerned with race, gender, and disability, are remembered and represented. Writing and composition often engage challenging, difficult, and controversial topics, and outcomes for learning certainly do not always develop exactly as instructors would like them to (Miller, 1994). It is important, however, that issues such as these not deter composition instructors in their commitments to justice, advocacy, and activism, though these commitments certainly present challenges that must be carefully considered.

Participatory culture demands that film technologies be utilized by not only experts, but also by everyday citizens who are not quite amateurs either. Contemporary citizenship and rhetorical dexterity cannot be understood uncoupled from the modes and apparatuses in which they are distributed, and this includes online video forums. Sheridan, Ridolfo, and Michel (2012) contend that “ordinary rhetors should appropriate the rhetorical tools of graphic designers, illustrators, photographers, and videographers in order to assume responsibility for the production of culture” (xii). If we as instructors in higher education can realize, even partially, the democratization of visual-technological tools in our classrooms, our communities, and in our public forums, we may be well on our way to ensuring students are equipped to be the cameraphone composers, the democratic participants, that contemporary information ecologies demand. The Retold Histories of Clemson assembles student rhetorical production, multimodal technologies, histories of race and racism, and modes of public communication to practice advocacy through documentary filmmaking in the FYC course.

Download PDF

Download PDF