Cameraphone Composition: Documentary Filmmaking as Civic-Rhetorical Action in First-Year Composition

by Jacob D. Richter | Xchanges 16.1, Spring 2021

Contents

The Retold Histories of Clemson

The Process: Making Documentary Videos in the FYC Classroom

The Retold Histories of Clemson: Three Documentary Films

Behind the Scenes”: Access, Accessibility, & Audiences

Appendix A: Assignment Prompt for The Retold Histories of Clemson Project

The Retold Histories of Clemson: Three Documentary Films

The films comprising The Retold Histories of Clemson probe a variety of exigencies and imagine a variety of publics as potential audiences, enacting in participatory fashion Gries’s imperative to design situations in which the student’s rhetorical process might “assemble publics.” Specifically, students composed with an eye toward not only their local campus community, largely composed of students not originally from Clemson or from South Carolina, but also to the larger communities in Pickens, Greenville, and Oconee counties who might potentially see their video creations. In this way, students assembled local communities in a way that allows a plurality of voices to arise and emerge publicly, which to some extent performs the work of documenting partial, incomplete, tentative, and nonetheless important understandings of a place and a community (Carter and Conrad, 2012).

Student Film #1: Crash Course Clemson

One student film, titled Crash Course Clemson, spoofs the popular YouTube channel Crash Course created by fiction author John Green. Crash Course narrates various historical events in short 10-15 minute episodes, using animation, humor, and the celebrity contacts of its star hosts to make videos the creators hope “will be useful to people,” altogether abiding by the “old-fashioned idea that learning should be fun” (“Crash Course Introduction”). Crash Course Clemson mimics familiar tropes from the YouTube series: the host rolling in on an office chair, the presence of tongue-in-cheek corny jokes, a globe placed nonchalantly on a desk. Like the original video series, the student remix then goes on to review past events, important narratives, pivotal moments, and key historical characters. In this case, Crash Course Clemson details the life and legacy of Benjamin Tilman, an avowed white supremacist who served as a United States Senator as well as Governor of South Carolina. Tillman was instrumental in the founding of Clemson University, and various buildings and landmarks on the campus still reference his name, including Tillman Hall, which still stands on the campus’s west side and is perhaps its most well-known historical building.

Originally named “Old Main,” the building was re-named after Tillman in 1946. Later on, as the student filmmakers outline in Crash Course Clemson, a movement arose in local communities calling attention to Tillman’s openly pro-slavery and otherwise racist agendas, culminating in calls to remove Tillman’s name from the building and to return it to its former name. In 2020, University administrators finally petitioned to the state of South Carolina for the name of the building to be returned to Old Main. The student film chronicles these issues and movements, providing their own commentary along the way, including a recounting of events important to them, including the graduation of Clemson’s first African American student in 1965.

Mobilizing various local and global publics, histories from an array of perspectives, and material and technological infrastructures, the student producers of Crash Course Clemson articulate a progressive, anti-racist history of their community, furthering the civic-participatory goals of the project through a willingness to engage with multimodal tools.

Student Film #2: Clemson’s History with Racial Discrimination

Another student film comprising The Retold Histories of Clemson project tells a story of the community’s history that holistically connects past and present, and provides a visual tour of the aforementioned Old Main building as well as footage of spaces that are of more recent prominence, such as the university’s football stadium. Clemson’s History with Racial Discrimination showcases the enduring legacies of slavery and its impacts on local communities, especially commenting on labor structures that used indentured servitude and convict labor to disproportionately exploit African Americans as workers. The history chronicled by Clemson’s History with Racial Discrimination then moves into a critique of anti-integration rhetoric in the 20th century, and finally begins exploring the disconnect between the University’s athletic success in football and basketball fueled by a majority African American student athlete body, comparing it to the university’s lagging representation of people of color on its campus as a whole.

This final point serves as an illustrative example of a trend that a number of student projects decided to engage in: exploration of historical events, peoples, and practices in the 19th and 20th centuries, which are then contrasted with the ways in which those events are remembered (or, alternatively, not remembered) today, followed by further exploration of various connections between past and present. For instance, Clemson’s History with Racial Discrimination ties Clemson’s history as a plantation and as a University that did not admit an African American student until 1963 directly to current issues with race, representation, and inclusion that still exist on campus today. Most prominently, these issues include the University’s failure to cultivate a more diverse student body, as well as its financial profiting from athletics teams that are predominantly composed of African American student athletes who are not paid for their labor, but who provide publicity, marketing, and other profit generating opportunities for the University. Clemson’s History with Racial Discrimination ends by speculating on ways students, faculty, and other community members can better remember and confront the enduring histories of their communities, calling on community members to each do their part to more actively engage with these important histories.

Student Film #3: The Untold History of Clemson University

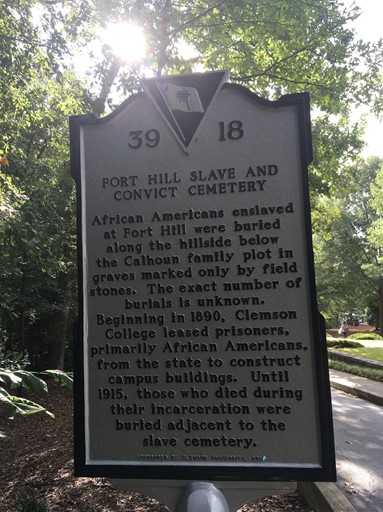

A third film that was produced by students is titled The Untold History of Clemson University. This film takes a slightly different angle than Crash Course Clemson and Clemson’s History with Racial Discrimination, focusing on the founding of the University and its early years in the 1880s and 1890s. Prominently, this film recounts how even after the abolition of slavery with the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, many African American citizens worked on an involuntary basis to lay the foundation for what would one day be known as Clemson University. Importantly, these students tie the history of the land the University sits on now to not only its history as a former plantation, but also to the founding of the University in buildings constructed by predominantly African American workers, especially convict laborers. The students who produced The Untold History of Clemson University show visually in their film the historical markers and testimonials that these abhorrent labor conditions and violent histories have left on the campus even today. The numerous images that the film showcases include an image that a student took of a historical marker showcasing the Fort Hill Slave and Convict Cemetery on campus, where at least 200 African American laborers are buried (Nicholson, 2020) (See Fig. 3).

In this way, the students who produced this film not only confronted the dominant histories of their University that they are generally accustomed to hearing about, but also looked beneath it and considered how the University was built, who it primarily served in the past, and which groups of people continue to benefit from its support. Additionally, students grappled with the often hidden, frequently unseen histories that helped to create their local campus community, many of which are oftentimes subsumed by more glamorous, uncomplicated narratives of place and identity. Unsurprisingly, many students were forced to confront uncomfortable questions of privilege, identity, and community. A number of students remarked that they had walked by the Fort Hill Slave and Convict Cemetery on campus before, and had not noticed it or known what it was (the cemetery is located near a popular parking lot on campus). The students who produced The Untold History of Clemson University took great care to convey to the viewers of their films that the legacies of racism, economic exploitation, and bigotry are still very much with the campus community today, going so far as to list and show photographs of buildings still standing on campus that were constructed by enslaved or convict laborers, many of which still host classes and University functions.

Other Student Films

Other films created for the project feature interviews with fellow students, showcase historical landmarks around campus, discuss local legends and narratives, contextualize the University’s success within athletics in relation to its histories, and further probe the ways in which a community’s history can be written, and re-written, with strategic attention to who those histories serve and what values are foregrounded in that particular telling. Student filmmakers interviewed fellow students to reveal current attitudes, and articulated arguments through visual, audio, and other rhetorical choices. Lastly, a few groups decided to diverge slightly from the predominant thematic topics many of their classmates pursued, instead engaging secondary options the project suggested, including a revisitation of Clemson University’s history of gender-based exclusionary practices and admission of women to the campus. Here, flexible project design allowed student interests to drive the multimedia productions, putting rhetorical power in the hands of students and allowing them to communicate the histories that mattered to them to the public at large. The assignment prompt for The Retold Histories of Clemson can be found in Appendix A.

Many project design choices helped The Retold Histories of Clemson to be successful, and similarly many choices would certainly benefit from further thought if repeated in future public advocacy project iterations. The particular application or program students use to edit and assemble their films will inevitably impact the filmmaking process and the distributed films themselves. The high degree of interaction student filmmakers have with particular applications and interfaces as they move through the filmmaking process requires them to function as technology critics in addition to technology users, including the political and ideological implications of the technological tools available to them (Selfe and Selfe, 69). Though as an instructor I certainly would define most projects that were submitted as having been “successful” simply through the production of new narratives on important community topics, in future iterations of this project, I hope to do more to push students to define what “success” in this project means to them, as it can certainly take on a variety of forms depending on goal, audience, and context.

Why Make Films?

Filmmaking in particular offered The Retold Histories of Clemson three primary affordances. First, to accomplish our primary goals of engaging the varied publics that surround our immediate local context, including our University, the class and I decided a visual component was necessary if we wanted to invoke symbols of local community or public memory, such as the historic buildings on campus or famed athletic stadiums. In other words, to resonate with potential members of our base audience, we needed to reach them not just through our historical or advocacy messages, but with messages of shared community and neighborhood familiarity as well. Second, we knew we wanted our final multimodal project to be collaborative, and this necessitated a project design that would maximize practical acquisition of new skills (such as how to use a camera or a microphone) as well as productive transfer of old skills practiced earlier in the course (such as how to revise for consistency or how to format citations for video end credits). Lastly, the class knew it to be important to engage as large and diverse of an audience as possible if our ultimate goals were to be communicated to the public at large, and video formatted for digital distribution and circulation streams such as those found on social media forums like YouTube and Vimeo seemed the most appropriate way to do so. Our approach was calculated and goal oriented.

After the films were created, they were uploaded to a free Wordpress website. This site was public, searchable, and open to be viewed by public audiences (the site was removed from the public domain shortly after the academic year came to a close). The choice to make the project public for the duration of the semester, but private after the semester drew to a close, was one that was made democratically by each class. Additionally, the classes and I also discussed whether we wanted the projects to be featured in academic publications. Ultimately, the class decided it was best to describe the projects in publications, but to not directly feature them, which is why this article does not link to the projects directly. Distribution in the digital age requires far more than simply being uploaded to the internet, however. Henry Jenkins (2006) characterizes participatory distribution on video-supporting platforms as containing a three-stage process of “production, selection, and distribution” (275). In other words, these videos and the Wordpress website must be distributed elsewhere, or else risk being available but unutilized, thus endangering the sense of authenticity within the production process. As Jenkins points out, participatory creators as well as their audiences must always make choices about how to share and broadcast their creations in strategic, deliberate ways.

These questions of delivery, distribution, and circulation of the site were discussed by each iteration of the FYC course, and students settled on different answers for how they would like to go about circulating their videos and the website as a whole to potential audiences. Some students chose to post their videos to their personal Facebook and Twitter pages. Others shared their videos to the local subReddit page, /r/Clemson. As a group, we considered creating social media accounts for the compiled project website itself, though we decided against this due to concerns about how public audiences might react to difficult conversations about race and community responsibility in what is still a very conservative part of the United States. These conversations, we decided, would be more productively discussed in spaces and forums outside of social media sites, at least for the compiled website containing all of the videos. Lastly, I shared The Retold Histories of Clemson website to both an email list and a Facebook group of fellow writing teachers at our university, some who have shown the videos to their own courses and students, including in distance-learning courses outside of South Carolina and our immediate communities.

Upon completing this project, I made it known to students that they were in no way required to make their video creations public and have them posted to the Wordpress website that I had set up. Regardless of whether the actual product was genuinely made public, the project required that students imagine a public audience, even if in reality the public would not actually be able to view their final documentary film. In this case, very real concerns about privacy, publicity, and student agency needed to be considered. As an instructor, I see a great deal of value in creating public representations of histories, values, and narratives, but I also wanted to be sure to respect the wishes, desires, and levels of comfort that students had with making the artifacts public, as well as the very real risks that can accompany participation in online forums (Reyman and Sparby, 2020). A few groups opted to not include their compositions on the final website, and students were allowed to switch groups early on in the arc of the project if they disagreed with their first group’s choice regarding the level of publicity for their film. As with many projects that engage the public, transparency, honesty, compassion, care, and instructor flexibility generally go a long way toward making sure all students feel supported and comfortable with any of the choices that they might make.

While The Retold Histories of Clemson website remained active and public throughout the duration of the project, after the project’s completion in the Spring semester of 2019, I made the site private and removed it from public circulation.

Download PDF

Download PDF