Bad Sex vs. No Sex: The Rhetoric of Heteronormative Temporality in Utah’s Abstinence-Based Education

by Nina Feng | Xchanges 16.1, Spring 2021

Contents

History of Abstinence Education in the United States and Utah’s Sex Education

Methods of Queer Linguistics and CDA: The Construction of Heteronormative Temporality

The Introductory PowerPoint: Heteronormative Parameters of Utah’s Sex Education Material

Junior High (JH) and High School (HS) Resource Guides: Heteronormativity vs. “Bad Sex”

The Introductory PowerPoint: Heteronormative Parameters of Utah’s Sex Education Material

The introductory “Health Sexuality Education Review” PowerPoint for teachers was the first document I encountered. For adolescents in Utah public schools, the PowerPoint establishes the heteronormative parameters of the education materials. Though students are not supposed to see this document, the information restricts the content that instructors may teach. On the first slide of the presentation, abstinence before marriage, or the avoidance of sex before marriage, is emphasized: “Utah State Law Mandates 53A-13-101. (1)(b) That instruction shall stress the importance of abstinence from all sexual activity before marriage and fidelity after marriage as methods for preventing certain communicable diseases” (USOE PPT). “Inappropriate” behaviors should be avoided, like sex before marriage; the consequence suggested is the contraction of a disease. These behaviors are expounded on in further restrictions. On four slides, the topics teachers should avoid are highlighted (I bolded the information on the slides):

The State Board of Education Rule and Utah State Law Mandates “The following 4 things may NOT be taught:

1. The intricacies of intercourse, sexual stimulation, or erotic behavior;

- Any questions that ask “how to” do something that relates to intercourse or sexual behavior falls under this category.

- We do not describe any sexual behavior. You may define behaviors such as: oral sex, sexual intercourse, for clarification.

2. The advocacy of homosexuality;

- Teachers can define and discuss homosexuality as it relates to their curriculum.

3. The advocacy or encouragement of contraceptive methods or devices;

- Teachers may teach about contraception, rates of effectiveness, where to purchase them, which need a prescription, etc. if it is part of their curriculum.

- Parental consent is always needed.

4. The advocacy of sexual activity outside of marriage;” (USOE PPT)

This string of restrictions and explanations presents a logic of mathematical transitivity. The first slide suggests that since state law mandates emphasis on abstinence, sex before marriage may be unlawful, or at the very least, inappropriate. If the advocacy of contraception and "homosexuality" fall into the same category as advocacy of sex outside marriage, these behaviors also seem inappropriate, or unlawful. These parameters define the heteronormative scope of Utah’s sexuality education, excluding people who are queer and unmarried sexually active people. The limits on the discussion of contraception also suggest that it is either not appropriate to use or it is not appropriate to discuss, along with sexual behavior in general. To acknowledge the existence but deny the details of contraception and sex teaches students the state-approved boundaries of appropriate discourse about sex. This heteronormative discourse maintains a continuing theme of absence throughout the documents: absence of sex before marriage, absence of "homosexuality," absence of contraceptive use, and absence of what sexual behavior consists of.

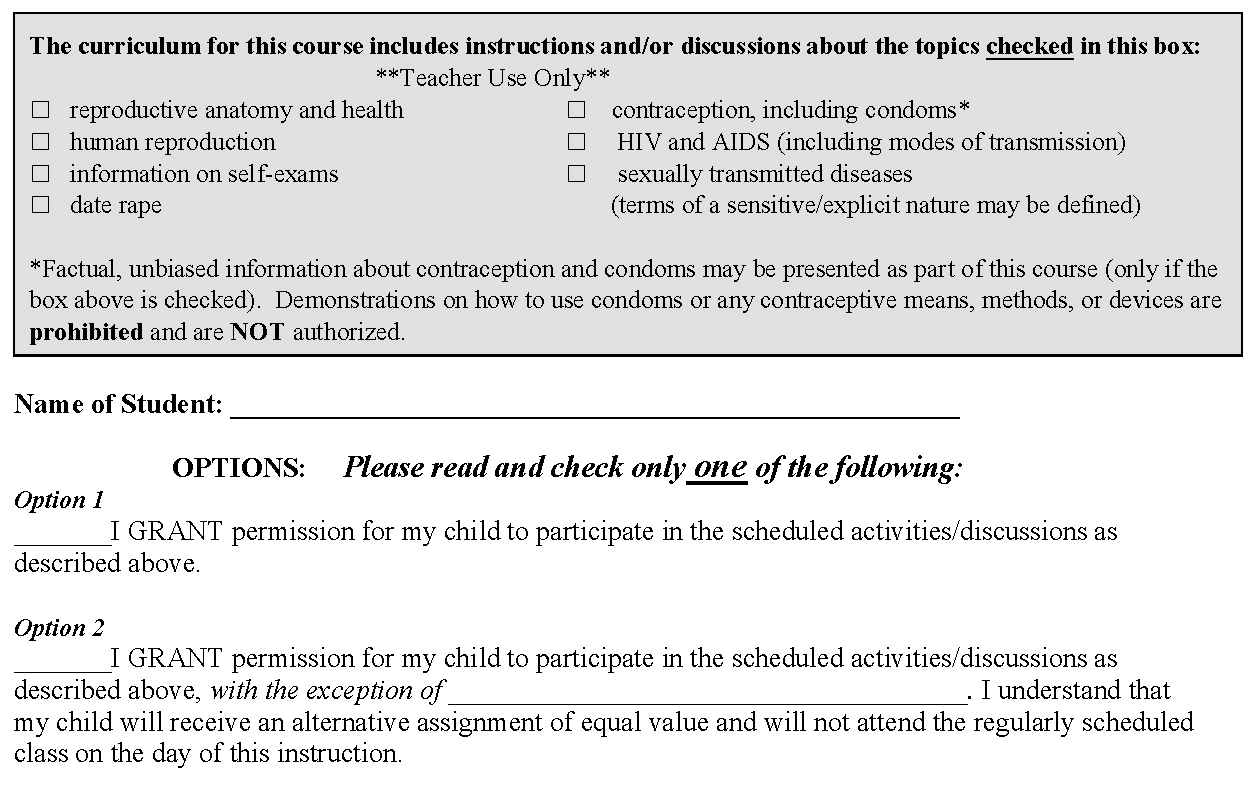

The PowerPoint presentation also notes the necessity of parental consent, as shown in Figure 1.

Parents are allowed to exclude their child from any curriculum about reproductive health, reproduction, self-exams, date rape, contraception, HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted diseases. The optional nature of these topics suggests that students do not need education in these areas. Most of these topics are also attached to areas of sexuality with negative connotations, such as breast/testicular cancer (self-exams), date rape, STDs and HIV/AIDS. These optional topics are in direct contrast with required education on “abstinence before marriage and fidelity after marriage” (USOE PPT). This suggests that if students stay within the heteronormative realm of abstinence education, they will receive all necessary knowledge, excluding unnecessary and avoidable knowledge of “bad” sex effects/acts/conditions.

The materials emphasize absence and abstinence again in the section titled “Tough Commonly Asked Questions.” The questions and italicized responses follow (I bolded the information on the slides):

1. How do gay people have sex?

This is a how-to question, but like with heterosexual couples, intimate behavior shared by homosexual couples is personal information which need not be discussed.2. Is masturbation dangerous or bad?

There is no scientific evidence that masturbation is dangerous. In segments of some communities and with some families, masturbation often becomes a moral issue where it is labeled as “bad”. What might be right or acceptable for one person isn’t necessarily right or acceptable for another.3. What is the best way to put on a condom?

Instructions for condom use are clearly indicated on the condom packaging label.4. Can you get pregnant from having oral sex?

No. The only way you can become pregnant is through vaginal intercourse. You may transmit or receive sexually transmitted diseases from oral sex however.5. I hear less and less about AIDS. Is there an AIDS vaccination to protect people?

No. Although drugs have been developed to manage the disease and ensure a longer life for those having it, AIDS creates many complications and is still a death sentence for those contracting it. There is no cure.6. What is the best form of birth control?

Abstinence from sexual behavior is the only 100% method of birth control. All other methods fail to some extent.7. Did you have sex before you were married?

I’m sorry, but as I indicated in the ground rules, I do not answer questions about my personal experiences.8. Can girls get pregnant if they do it standing up?

Girls can become pregnant regardless of the position they are in when they have sexual intercourse.9. Can you lose your virginity by using a tampon?

People define virginity in different ways, but most define a virgin as one who has never had sexual intercourse. Using this definition, you cannot lose your virginity by using a tampon.10. Will using a condom prevent a sexually transmitted disease?

Abstinence is the only 100% sure method of preventing STDs. The CDC has indicated that condoms do offer some protection against the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases.

These questions are representative of the student discourse in sex education, and though they are directed at the instructor, they also once again mark the boundaries of appropriate discussion with students. Many of the answers require the instructor either to refuse to answer (“I do not answer questions about my personal experiences”), answer vaguely (“What might be right or acceptable for one person isn’t necessarily right or acceptable for another”), or answer advocating abstinence (“Abstinence from sexual behavior is the only 100% method of birth control. All other methods fail to some extent”). Students are redirected again and again to a realm absent of sexuality where abstinence provides safety, birth control does not need to be discussed, and virginity is a prized characteristic for those who menstruate (“Can you lose your virginity by using a tampon?”). The idea of AIDS bolsters the boundary by becoming an elusive monster existing outside the walls of abstinence, retaining the fearful rhetoric of the 1980s AIDS epidemic with the phrase “death sentence,” with HIV ignored as a treatable medical condition. J. Blake Scott discusses the rhetoric of contamination in Risky Rhetoric: AIDS and the Cultural Practices of HIV Testing, where HIV is conflated with its carriers, particularly gay men, who are depicted as inherently promiscuous, deviant, and risky. From this perspective, queerness itself becomes dangerous (41). Scott’s work exposes the vilifying rhetoric of "homosexuality," but this rhetoric creates the same binary and essentializing effect as the rhetoric of heteronormativity in the sex education materials—the heteronormative world of abstinence becomes safer, cleaner, and inherently filled with potential, the more the queer world of sex is polluted with risk, fear and inherently paired with death.

The Utah sex education materials emphasize a world devoid of sex and therefore devoid of dangerous sexual effects and conditions of sexual bodies. As we will see from the junior high and high school materials, two motifs emerge with the reappearance of word patterns: “future” versus “sex.” Heteronormative temporality becomes evident as lexical cohesion makes these themes prominent. Abstinence operates to further heteronormativity and a “healthy” future, whereas sex outside marriage is associated with negative language, and the lack of a future.

Download PDF

Download PDF