An Everyman Inside of a Superman: A Cluster Analysis of Action Comics #1

by Rebekah Hayes | Xchanges 18.1/2, Spring 2024

Contents

The Artifact

Action Comics #1 was published in 1938 and contains stories other than the origin of Superman, but for the purpose of this study, only Superman’s narrative will be analyzed. Action Comics #1 begins by describing Superman’s origin on a distant, culturally, and scientifically advanced planet (Siegel and Schuster). Infant Superman is rocketed to Earth, taken in by an orphanage, and begins to exhibit extraordinary powers and promises to help humanity. The first narrative features Superman locating proof of innocence for a woman on death row, leading him to barge into the governor’s home to obtain the woman’s pardon. In the second narrative, Clark Kent hears of an abuse case. He becomes Superman and confronts the man abusing his wife. Later, Clark asks Lois Lane, his coworker at the newspaper, to go dancing with him and she reluctantly agrees. An aggressive man, named Butch, tries to force Lois to dance with him, and Clark passively defends her. When Lois leaves Clark at the roadhouse, she is followed and kidnapped by Butch. Subsequently, Superman pursues Butch’s green car, and Superman hoists Butch onto telephone lines. In the next narrative, the newspaper editor sends Clark to Washington D.C. After listening to a lobbyist, named Greer, coercing a senator to vote for wartime interference, Superman follows Greer and carries him through the heights of the Capitol to terrorize him into altering his behavior.

Visual Cluster Analysis

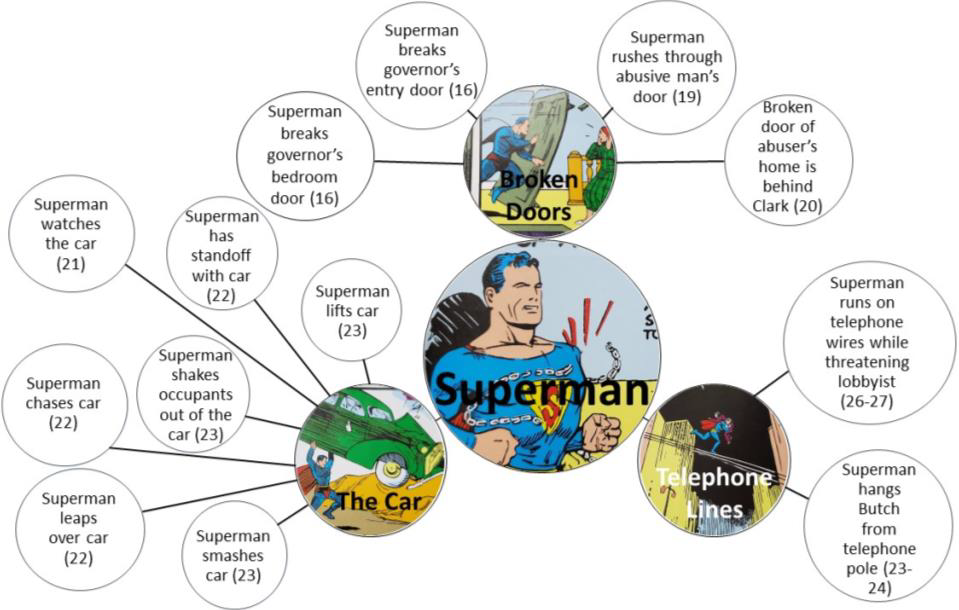

As previously discussed, to limit the scope of this project, “Superman” and “Clark Kent” will be the key term in this cluster analysis. The character is prominent throughout Action Comics #1 as the focal point of each part of the narrative, making him meet Foss’s rule of “frequency and intensity” (67). Much discussion of Superman’s costume and appearance has already been conducted nullifying the use of these details as providing new context through cluster criticism. Also, because Superman is in nearly every panel, visuals cluster around him easily, increasing the importance of “frequency and intensity” in identifying visual cluster terms associated with him. In order to identify viable visual clusters, Foss’s description of identifying clustered terms in the form of “representational images” is implemented in the identification of cluster terms (65). Around Superman, the following visual cluster terms have been identified: the green car, broken doors, and telephone lines (see fig. 1).

The Green Car

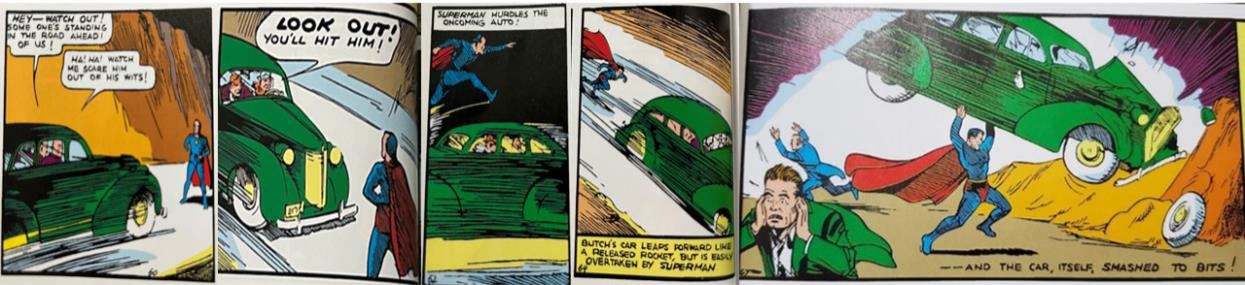

Arguably the most prominent and identifiable cluster term associated with Superman is the iconic green car. Featured on the cover of Action Comics #1 and a vital part of Superman’s pursuit to rescue Lois, the green automobile meets Foss’s guideline of intensity (see Figure 2). Superman is frequently framed with the vehicle from the moment of its introduction (Siegel and Schuster 21-23). However, the negative use of the car and Superman’s interactions with it suggest Superman is opposed to the rhetoric embedded in this automobile.

Before the most famous panel in which Superman smashes the car, Superman was shown pursuing the car. First, he stood in front of the vehicle, almost daring the car to run him over; then, he leapt over the speeding vehicle, allowing him to chase it, capture it, and shake the occupants violently from the interior (Siegel and Schuster 22-23). Next, in a replication of the cover (except for the missing third man cowering in fear), Superman raises the car above his head in a move of impossible strength. In this panel, the front of the car is slightly crumpled, showing Superman has already begun to shatter the car (see Figure 2). Multiple motion lines along the sides of the car represent the downward motion and incredible speed at which Superman is breaking the vehicle (see Figure 2). Screaming men flee away from Superman and this terrifying scene ends with Butch running towards the reader (see Figure 2). While the textual narrative has assured readers that Superman is the protagonist and a paragon of virtue, each visual detail reveals strength, speed, destruction, and terror that evokes a sense that Superman is dangerous.

Within this panel, the car has come to represent the power, status, and control that Butch and his companions had exerted, but are now made impotent by Superman’s power. Subtle evidence made the car a representation of Butch’s control. Of course, Butch’s suit matches the car and signals a relationship between the two, but it is his use of the car that signals its relationship to Butch’s control. The symbolism of control is particularly clear in the previous panels in which the car was the weapon Butch attempted to level at Superman when attempting to run him down (Siegel and Schuster 22). In these panels, the action flows against expectation as Superman is on the right side of the panels and the green car moves from the left toward the right. The expectation would be for the protagonist to move left to right as this is the direction American comics are read (Potts 91). Thus, putting the car on the side of panels usually occupied by protagonists indicates it has greater narrative beyond the power of a singular man, Superman.

However, when Superman leaps over the car the action is reversed. In the third panel in Figure 2, the car appears to be heading in a different direction, yet it remains on the same path. This disruption in “action flow,” which is the consistency of direction in comic books, supports that the physical weapon of the car loses its power over Superman. In comics, artists can choose to “have all protagonists in a story move with that natural left-to-right eye flow until the protagonist . . . experiences a reversal in his or her journey” (Potts 91). Although Potts suggests there is flexibility in the variety of ways that artists can use the reversal of action flow, it seems Superman’s leap over the car signals a switch from Butch having control to Superman possessing greater influence. Additionally, the camera switch converts Superman from passively standing to becoming aggressive and frightening to the men. Specifically, in the iconic panel, Superman literally wrests Butch’s power from him, shatters that symbol of control, and terrifies the occupants who were using their power to take people like Lois. Thus, Superman’s destruction of the green car is an assault on toxic uses of control achieved through wealth and proves he is equally dangerous to its occupant for whom it is a symbol.

Additionally, within the historical context of Siegel and Schuster’s writing, the car is symbolic of an industry that wasted the city of Cleveland and an instrument of alienation. Siegel and Schuster’s home city of Cleveland had significant negative associations with the automobile industry, “six motor manufacturers were based [t]here in the decades after 1900. The 1930s Depression, however, initiated a period in which the decline of its industrial base destroyed much of Cleveland's economic strength” (“Cleveland”). Meaning, in the home city of Superman’s creators, the widespread economic downturn in the automobile industry was detrimental, causing automobiles to represent the loss of economic stability.

Furthermore, during this era the automobile was connected to alienation of people from other drivers and pedestrians. The invention of the stoplight in Cleveland showed how cars could be a source of disconnection among people (Nelson 1). Thus, the car represents both the economic devastation of the Great Depression and the individual’s alienation from humanity. So, when the lay reader viewed the car, connotations of economic downturns and distance from other people were evident. This is furthered when considering how the car is used as a tool to try to run down an individual in the road. The alienation that was associated with the car dividing the ability to recognize others’ humanity is understood through the attempt to kill Superman. Thus, Superman’s destruction of this symbol places him in the position of adversary to the rhetoric embedded within this cluster term. Superman’s rhetorical opposition to the powerful is evident through his taking their control, status, and power from them, and the same action conveys opposition to loss of livelihoods and supports connection with humanity.

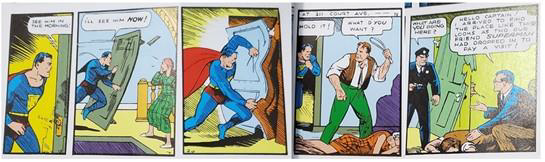

Broken Doors

Another frequent and intense cluster around Superman is the three broken doors involved in his storyline. These doors each hold rhetorical meaning that can be apparent to the average reader: Superman breaks barriers. However, the doorways also reveal an underlying meaning that Superman is a character who cannot be held back and can invade every aspect of people’s lives. The repeated action of breaking doors shows readers Superman can splinter barriers that keep the average man from intervening in specific aspects of life. “Breaking barriers” is the phrase that seeing this frequent action evokes, reminding readers of normative barriers preventing people from going outside of accepted norms. Each door seems to represent a different barrier that Superman implies should be ignored, and, as a “superior” human, Superman does ignore them, asking readers to consider the possibility that these barriers are wrong and should be removed.

First, the door to the governor’s house seems to represent barriers to justice because Superman breaks this door to retrieve a pardon (Siegel and Schuster 16-17). Superman jumps through this door, but it remains intact, although separated from its doorway, implying the barrier is a problem that remains, but Superman is capable of overcoming it (see Figure 3). This meaning correlates with Superman’s vow to help those in need. The door to the governor’s bedroom is representative of the need for citizens to have access to their political representatives and not be ignored and barred from being heard. Interestingly, this door is made of metal and should be the most difficult to breach (see Figure 3). Because this door crumples in Superman’s hands rather than flying off its hinges or shattering like the other doors, this barrier is the strongest and the most challenging to Superman (see Figure 3). There is a possible suggestion that it bends rather than breaks because the law must be accessible and adaptable to individual situations rather than an inflexible source of punishment. Further, although it does crumple under Superman’s grip, it was not as easily removed even by Superman, telling readers, while Superman can triumph over the barriers to leaders, the barrier is that much greater to the normal citizen (see Figure 3).

Regarding the door Superman breaks to stop the man beating his wife, this barrier represents the normative perspectives from the era in which spousal abuse was to be ignored or accepted. This door is made of wood and the reader can see a portion of the door is gone when Clark is kneeling over the defeated man (see Figure 3). The rhetoric involved in this particular barrier is especially clear when examining the panel in which Clark is told that there is a report of a man abusing his wife, appearing to run directly from this panel to the next as Superman, in which we do not see the door, only Superman’s immediate intervention. Scott McCloud theorizes the space between panels, the gutters, represents a space in which readers create the scene for themselves (88-93). When the reader must fill more of the gap, it requires more effort and the shot that Siegel and Schuster use between Clark hearing about the abuse and his intervention as Superman is considered a “scene-to-scene” transition (McCloud 74). Although the reader must assume the leap to the location of the abuse, the connection between Clark and Superman makes it easier to fill the gap. Thus, the ease of the transition implies that this door or barrier that Superman can overcome is so thin people can easily see through it and take action. However, the barrier does exist, and the door must be opened to recognize and act on the issue. Superman’s interactions with this door compel readers to reinterpret their perspectives on physical abuse and consider recognizing when abuse is happening, and then act on that recognition.

Furthermore, there is surprising meaning connected to the cluster of the door of the abusive man. Of note is the mirroring between the panel in which Superman arrives to stop the man beating his wife and the panel in which Clark leans over the man’s prone body (see Figure 3). While there are several panels between the moment Superman stops the man and the moment the officer arrives, the panels could be viewed as a set of “transitions featuring a single subject in distinct action-to-action progressions” because they each feature Superman and the abusive man fighting (McCloud 70). This creates contrast when there is no longer action between Superman and the abusive man because Superman changed back to Clark and adopts a position similar to the one that the abusive man had held when Superman arrived, and the man has taken the position of his prone wife. In the same panel, the police officer becomes the subject in action evidenced by his mirroring Superman’s arrival and his addition to the scene.

In addition to simply mirroring each other, the role changes become alarming when considering the underlying, likely unintentional, rhetoric about the cycle of abuse. By attacking the man, Superman became the abuser, injuring the man the way the wife was injured. The police officer taking the position of Superman, by entering through the door, has a connotation that perhaps the police, like Superman, may have interest in justice, but can be instruments of injustice. This door is complex visual rhetoric that could be interpreted as a positive message about intervening in abuse, but it also reveals the dangers of assuming the role of avenger. Ultimately, the cohesive message that arises from this cluster of doors around Superman is that Superman stands against norms, representing anti-normative narratives, which is both frightening and a call to action against these barriers.

Telephone Lines

Another cluster group around Superman is telephone poles and their wires. They are twice shown as Superman’s apparent method of punishment, making their appearance an intense association with Superman, and they appear frequently due to their presence in these multi-panel punishments (see Figure 4). To punish Butch, Superman climbs a telephone pole near the site of the car chase and hangs Butch from the telephone pole (see Figure 4). Later, to frighten Greer, the lobbyist, Superman leaps to the telephone wires in Washington D.C. and races across them (see Figure 4). These two instances show Superman’s ability to confidently climb the heights of telephone poles and touch their electrified wires. The repeated use of telephone poles demonstrates Superman’s intentional use of a fear tactic to enact retribution upon the villains he deems to have transgressed against society. This intense use of the telephone lines as a visual element invites readers to understand the rhetorical meaning of the telephone poles.

Although they are one cluster term, it seems each use of the telephone poles as punishment centers around slightly different rhetoric. With Butch’s punishment, he is hung from the pole and seemingly left there until someone releases him. In Greer’s punishment, Superman is racing across the wires and uses fear of electrocution to intimidate Greer, as seen in the dialogue where Greer fears this outcome and Superman toys with the possibility of being electrocuted (Siegel and Schuster 26-27). Thus, in Butch’s punishment, the importance of the telephone wires as a relatively great height is the focus and it results in a form of imprisonment because he is unable to free himself from this penalty. While Greer’s punishment focuses on the wires’ potential electrocution, the height is still important because Superman is racing over Washington, D.C., which imposes importance upon the height in this situation as well. Interestingly, Greer’s punishment is unresolved in Action Comics #1 because it ends on a cliffhanger, in which Superman leaps from the wires towards a build and claims he has “missed” the building, thereby intensifying the importance of heights because Greer is the one that would be harmed by the fall (Siegel and Schuster 27).

Additionally, the telephone poles’ rhetoric of dominance is evident through understanding their connection to heights. When a person or group has the high ground, it often means they are going to win an argument because they are morally superior, but this is a reference to battle tactics which have long presumed having the highest section of a battlefield will help assure victory (“Moral”). Thus, heights symbolize moral and physical dominance and superiority. Superman’s attitude toward the telephone wires can be understood in his trip with Greer up the telephone wires when Superman displays a half-smile to assure readers that he is confident and comfortable going to these heights (see Figure 4). Superman’s dominance over his opponents is clear because in each case the men are carried and do not have any control over where they are going while Superman is able to choose to take them to these heights. Superman’s moral superiority is given to readers through the narrative, but he is visually superior to the men because he has agency and control over them.

Furthermore, standing above a place and looking down, as Superman does from the telephone lines, is a classical act of dominance. In the panels in Washington, D.C., Superman takes this pose to gaze down at the Capitol building, a symbol of U.S. governance and ideology, implying his dominance over Greer, who is seemingly representative of corruption in the U.S., and the U.S. government (Siegel and Schuster 27). In Figure 4, the fourth panel is angled so it appears the viewer is looking up at Superman on the electrical wires and this angle is an “up-shot [which] is often used to convey their [characters’] strength” (Janson 105). Although the perspective is from a distance below Superman and Greer, creating a sense of height, the angle emphasizes Superman’s power. In his dominance and power, Superman’s punishment of Greer serves to assert that Superman will oppose corruption in the government, and he independently has the power to do so.

Importantly, Superman’s position on the telephone wires of Washington D.C. shows his dominance comes with perspective. The final panel, Figure 4, is from behind Superman and looks down on the Capitol building. He can view the Capitol and the intricacies of the government with a macroscopic perspective that shows him the danger of venal individuals in a society reliant upon the government acting in good faith (see Figure 4). Without Superman holding him, Greer would fall, indicating his inability to hold onto the larger impact of his actions on the Capitol. So, Superman’s secure perch at such a great height also argues he should have power because it grants him perspective to recognize corruption and act against it. Seemingly, Superman is dominant over his individual opponents and over the locations where he implements punishments. Meaning, when Superman enacts his justice on Butch from the heights of the telephone lines, he displays his superiority to Butch’s financial status and control.

Overall, Superman’s rhetorical dominance shown through the cluster of telephone poles appears purposefully intimidating. Superman’s continued role as an American symbol makes this rhetoric especially relevant. If Superman and America are dominant as pictured in Action Comics #1, then they will set the norm for what is unacceptable deviance. Without the examination of social or physical controls on Superman/America, they can dole their version of justice as an unimpeded imperialistic force. However, because Superman’s punishment is meant to strike fear in those he deems have transgressed against society, Siegel and Schuster’s visual grouping of telephone wires also suggests those who do not deviate from Superman’s vision of “good” have nothing to fear. In these panels, Superman is not punishing random people; he is enacting “justice” on people who are traditional symbols of corruption. Butch, as his name implies, shows an aggressive masculinity that takes whatever he wants and exerts economic privilege over the working class, and Greer represents a group of people trying to manipulate the political system for monetary gain. The greater message conveyed through Superman’s dominance is the people who take advantage of their political or economic positions may have had uncontested power, but they can be challenged and their influence disrupted.

Download PDF

Download PDF